John Baldessari.

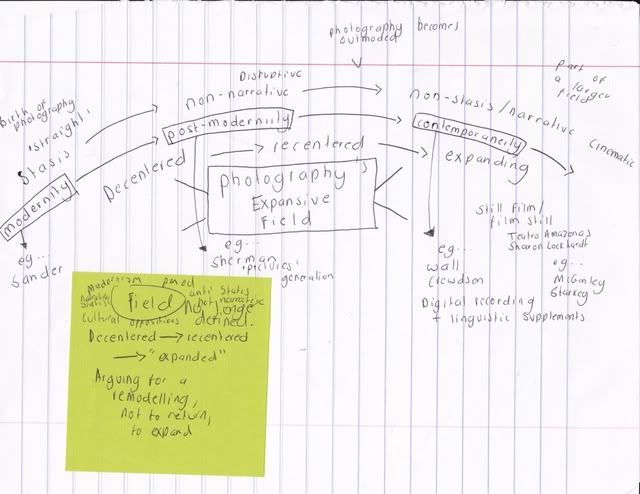

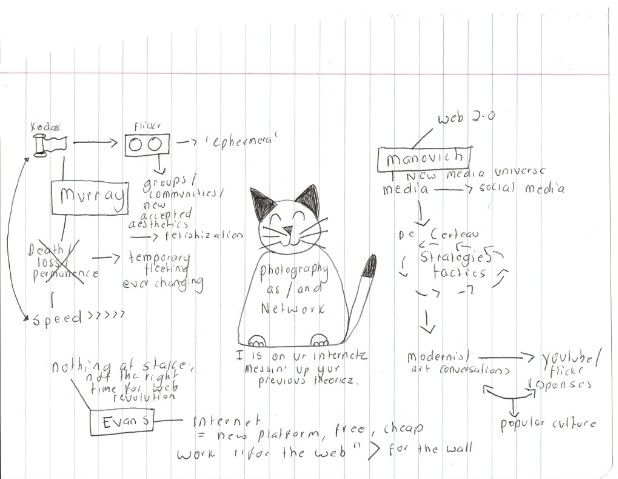

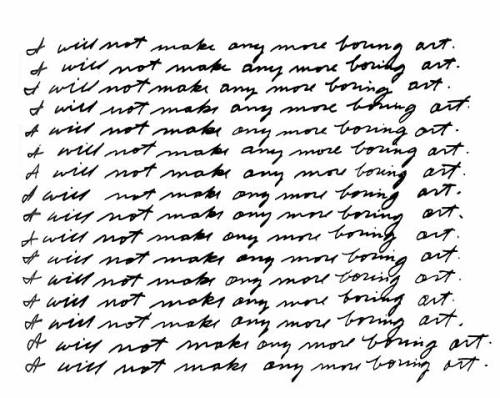

Many of the arguments posed in this symposium are rehashed and outdated theories that no longer even need to be discussed at this level - Jennifer Blessing discusses her belief as photography as indexical, Barthes and Stieglitz and Szarkowski are mentioned various times, there is talk of dying materials and digital manipulation. If the panel, by default of its members is assuming an educated audience, then half of the arguments are really already "over." This panel is dominated my white, male, western figures, also, which speaks volumes to me about the conception of photographic theory. This alone assumes those engaged are a part of an elite group of "accepted" photographers. Firstly, as Douglas Nickel observes, this is a problematic question because "photography" is an extremely loaded term. It depends on what we're talking about. The medium as a whole, historical views or theories on what photography supposedly is? "Photography over? More often these days, it feels like it's only just begun." This is what Vince Aletti claims and you know what? I want this to be true, but in reality, I'm not really a believer. I don't believe photography is "over", either. As many of these arguments display and as Lorca diCorcia brilliantly puts it, its just tired.

Tired indeed, I am very tired of hearing the same boring argument rehashed and redisplayed. The only person who really appealed to my sense of photography's place in art history was Beshty who makes an important argument that is often glossed over in photographic discourse. Art, not just photography, is a business, a money maker, an institute. Its planned and assembled into a neat degree programme and taught to you, marketed and sold to you. Beshty claims that the "crisis" of photography is one largely created by its critics, creators and teachers. He asks, why is there a visible segregation of photography departments within art school, when these distinctions do not exist in the contemporary art world? As for these distinctions not existing in the art world, I am not entirely in agreement, but I do whole heartedly agree that the segregation of photography from art in teaching institutions is infuriating. It is something I have always had a problem with and yes I would love for photography to be over and art to dominate. Why is painting, sculpture, performance art, etc lumped under "art and design" and photography is separate? I'm not a photographer, I'm an artist who enjoys making use of photography and desired to learn more about it then other mediums. Why then, is my only option to be isolated from the rest of the art world? If you disagree with this, take a walk over to the A&D building and realize how much you're missing out on.

Perhaps this is my own personal gripe and many of you may be content with just learning about photography and that's not my complaint. My concern is that by segregating departments in this way, photographers are essentially being pigeon holed into one area and isolated to a particular set of rules, standards and expectations and this, in my opinion, is artistic suicide. As Peter Galassi puts it "there is a difference between anything being possible and everything being the same." If photography constantly strives to be accepted as art, why is it so exclusive? As Corey Keller claims, calling yourself a photographer rather than an artist has a very layered connotation. Many may find comfort in being a part of their own special world, their own private room in the art hotel, but personally, I'm greedy and I want it all and I really wish learning institutions would facilitate this better. I think this would result in more interesting, radical and experimental work, better and more engaged arguments about photography and a new perspective of its relation to the larger art world.

Is photography over? Absolutely not. There are many photographers I've met who still believe they are making truth, who still believe large format cameras and the perfect print is the only way to make work, who align themselves with the Michael Frieds of the world and believe this is the only way to go. These people have remarkable talent, I am not denying this, (there's nothing wrong with making beautiful prints, of course, that's what we're here to learn!) I am simply pointing to the fact that there is a certain way "good" photography is positioned and this is far from being over. The cornering of photography as its own (often boringly conservative) medium in art schools is alive and well. There has been such a fuss kicked up about digital and the loss of materials, but the reality is nothing much has changed. Yes, it is really sad to see beautiful papers and films go and old processes fade out, but people are still using photography in a very similar, slow moving way. Photography is not radical enough (speaking in contemporary terms) to be over. After all, it matters as art as never before! After three years of studying photography I am a little jaded, so excuse my personal art baggage, but I think its all very blown out of proportion and Beshty is one few who points to the facts. Photography "for the wall" is nowhere near over. Some of the most radical or different work I have seen is that created by people not formally studying photography who are experimenting with the medium and this depresses me. Photography is not over, far from its just a bit stuck. Large, beautifully printed work is amazing, but its beginning to look far too similar and say less and less. Perhaps this is why my favourite photographers are those who have a complete and utter disregard for the preciousness of the medium and how it is supposed to work. I get more of a thrill out of looking at photography made by people from other areas of art, who are experimenting with the medium, rather than the work I see everyday in my own department. I seem to see more "new" ideas here. What does this say about Contemporary photography? I would love to know if I am alone in these thoughts (which I frequently find I am) or do others in the class share this view?