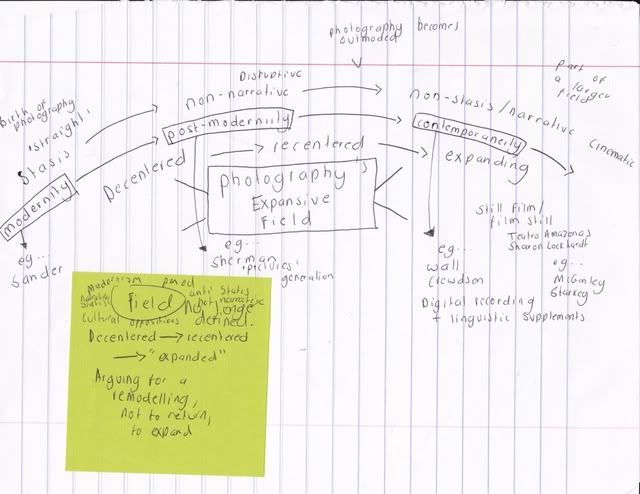

It seems that Baker's main claim is that photography is part of a continuously expanding field and what is essential, is a constant mapping and remapping of this process. He calls for a remodeling of a digram first employed by Krauss, instead of a return to old and dysfunctional theories of photography born out of Modernity and Post Modernity. He sees past theories as important but deems some editing, reshaping and reconsideration of such ways of thinking necessary. Baker's conclusion suggests photography's possibilities are infinite. He attempts to decipher past and current trends in photography in an effort to prove his claim that photography is not simply "stasis" or "non-stasis", nor "narrative" nor "non-narrative." He sees new photographic practice as now merging all four principles, thus expanding the field of photography, collaborating and integrating with other contemporary media, such as film, projection, etc. Baker claims photography becomes thought of as "outmoded technologically and displaced aesthetically." (122).

August Sander Three Peasants

Baker claims to understand photography's expanded field, we must consider the various oppositions in photography and how they have evolved over the years. Firstly, he discusses the tensions between Narrative and Stasis in photography, as seen in the work of August Sander. Photography has the power to ultimately freeze a moment in time, to capture what Barthes sees as the death of the moment. Simultaneously, the photograph is full of a whole new life, a life of social and scientific function, story telling, exploration, exploitation and confrontation. Baker sees photography's inherent "discursivity" (126) as an essential contradiction of its stillness and quietness. Baker sees contradictions too in the work of Sherman's Film Stills.

Cindy Sherman, 'Untitled Film Still'

Baker illustrates this through another diagram. Baker claims the "triumvirate" of great postmodern photographers birthed a new type of photography, that of the film still, or the still-film, the Cinematic. He claims this results in a "mad multiplication of cultural codes" (132). Baker sees this type of work as playing on narrative and not-narrative. I think there are endless examples of this type of work. There has been a trend for photographers to engage with the "in-between moment," a moment that is of not so noticeable, (at least in mainstream cinema) in the sense of on screen film, but can be employed and explored beautifully when borrowed by photography. This type of work is disregards the before and after and grips the spectator in an anxious moment of uncertainty paired with stunning visual technique and attention to detail. For example, the work of Hannah Starkey is clearly employing a cinematic aesthetic. As written by David Campany in his introduction to 'The Cinematic,' - "Still photography—cinema's ghostly parent—was eclipsed by the medium of film, but also set free. The rise of cinema obliged photography to make a virtue of its own stillness." I think Campany sums up the rise of this type of image, one that is taking advantage of its own power of narrative/non-narrative and stasis/non-stasis (I can't help but think of Fried's Theatricality/Anti-Theatricality here, also).

Hannah Starkey, "Untitled"

Hannah Starkey, "Untitled"

Baker sees it as of great importance and strengthening his theory, that this type of work is dependent on cinema, similarly to how other work is dependent on video, in order to function. Baker discusses the importance of the "talking picture" also, or the fusion of narrative and stasis. Here, Baker is discussing the a variety of work, from the "painterly depictions of digital montage" (134), (Wall, Davenport) to the Hollywood Tableaux (Crewdson), to pairing of images with sounds, text, projection, video, (Gerard Byrne, Douglas Gordon), in what he would call "narrative caption." Baker does a very admirable job in explaining to us that photography, or I would go as far to say any medium, can no longer be specifically object or aesthetically bound. Photography is a part of various movements, "genres" and art works. A telling example of this is how the Museum of Contemporary Photography just held a mainly video based exhibition, 'Mix Tapes and Mash Ups.' That the very name of that exhibition is borrowing terms from music and internet culture shows how widely spread photography is. I respect Baker's diagram, but I think Nancy Devonport who scribbled circles all over his diagram is the one who is really getting the point across best. Yes, we need maps, yes, documentation of a medium's evolution is very important, but we are moving at such a rapid rate, that it is almost impossible. It is our jobs as artists to look critically at these trends and incorporate them into our own practices. Why are we making large scale, cinematic prints? Why are we making work purely for the internet? What is causing these rifts? Mediums feed of one another and are inextricably linked. Baker makes a strong point when he states, "that this is a cultural as opposed to merely aesthetic field is something that certain recent attempts to recuperate object-bound notions of medium-specificity seem in potential danger of forgetting" (136).

Texts that attempt to summarize photography in one diagram, a few buzz phrases or theory can often frustrate me for two reasons. Firstly, the author's bias always dominates, secondly, there is always picking and choosing. I was relieved to see that, although Baker did mention the usual suspects, he didn't go all Fried on me (Jeff Wall is like, sooo dreamy) but he was careful to not get stuck in this and moved onto the importance of the medium. I think this is a really interesting way to view photographic history. In fact, I like the idea of removing all names and simply focussing on trends and overlap in specific media practice, perhaps using the formula suggested by Manovich in his recent lecture, then perhaps we could begin to relate certain trends to cultural factors, political factors, etc.

Whilst reading this and thinking about overlap of mediums, stasis/non stasis, narrative, none narrative I was thinking of the photographer Ryan McGinley and how his work provides a good example of much of what Baker is discussing for various reasons:

- McGinley's images provide an example of media crossover, as he is originally a graphic design artist who now makes use of video also.

- McGinley's images rely on a structure of non-stasis/non-narrative. They are what Fried would call "theatrical."

- There is no real story or sequential narrative in McGinley's images, much like the cinematic images that have been sprouting up over the last decade or so. These photographs, much like the work of Sherman in the her time, chews up popular culture and spits it back out, beautifully.

- McGinley's systematic use of the internet to promote his work adds a whole other layer to photography's expanding field, a layer which is ignored in Baker's text.

No comments:

Post a Comment