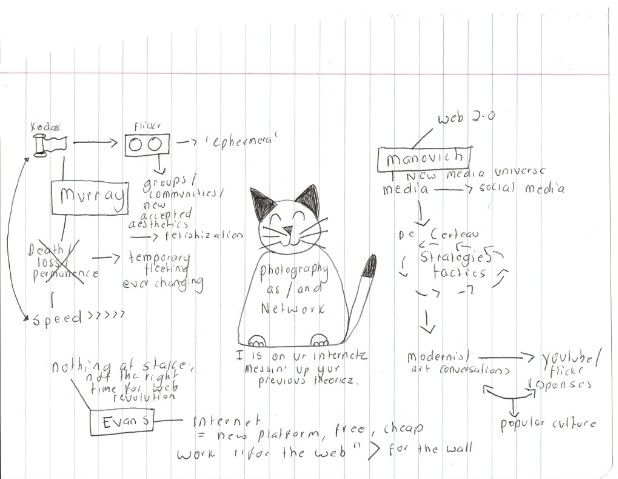

Flicker provides, is a case study of how contemporary photography has been deeply effected by practices of online social networking. For example, Murray mentions is the idea of ones "Flickr identity" which goes hand in hand with the sense of transience that characterizes online photo sharing. She discusses how a photographer can build a sense of his or her own style by adding to "a building block of a biographical or social narrative" (161). Online photography in the context of a regularly updated Flicker is not focussed on death, loss or preservation, but rather, the fleeting moment. A sense of permanent presentness is created in this online world and the addition of the "comment" function adds to the immediacy of this practice. A photographer can receive instant validation or criticism of his or her work, if that is what they desire. Murray seems to suggest that speed is one of the founding characteristics of the online photo sharing world. This reflects the ease of use provided by the digital camera or digital film scanner.

From the group 'Polaroid Cats' on Flicker.

In addition to the new temporal speed of photography, Murray discusses the roots of online photography and its connection to past photographic methods. She mentions the ease offered to consumers by the Kodak brownie from the 1880's and traces this all the way up to the present day. Certainly, this type of photo sharing began its acceleration a long time ago. As radical as it may seems to some, this is not an entirely new practice. Murray sees the progression of the Vernacular or snap shot aesthetic into a new online world as a departure from Victorian notions of photography and preservation, or the cameras ties to death. In fact, Murray claims we have landed in a new category of photography called 'Ephemera.' Oxford English Dictionary defines this as: "One who or something which has a transitory existence." Certainly, flicker is designed to be transitory. As Murray mentions, as each new batch of photographs are uploaded, old ones fade into the background and become and archive. This is a good example of the loss of the "preciousness" of photographs in this context. I the past, photographs of the dead were kept like sacred objects in beautifully decorated books as a direct connection to the dead family member. Now, family photographs are regularly posted online and constantly transitioning into the future, making each moment temporary and focussed on the now.

Murray also discusses the fetishization inherent in certain Flicker groups in the form of preference of certain colors, styles and themes over another. If you can imagine it, there is a group for it on Flicker. For example, see the Polaroid Cats group, two of my favourite things combined. This group strictly accepts real polaroids, explicitly stating "no poladroids" (incase you're unfamiliar, a polaroid is a digital photograph photoshopped to look like a polaroid and cropped into a frame of similar style to mock the aesthetic without having to actually use a polaroid camera) and only of cats. Murray also discusses in particular how Flicker has proven that theories of a "predicted loss of difference, mistakes, 'realness' in the photograph and filmic image that would come with the widespread use of digital image technologies" is in fact, not the case at all. Murray notes that many images have been in fact "fetishized for their low end look" (160). Murray is certainly correct about this. In response to the thousands of groups that favor a sleek, digital aesthetic, boasting the use of macro lenses and photoshop filters, etc (for example: see here), many set up groups that celebrate the unpredictability of film, along with the grain, the dust and even what happens when, as Murray discusses, digital photography doesn't play by the rules (see picture below). I can think of so many examples of this for class as I am certainly guilty for having an attraction to a less sleek and clean image (I am definitely not disregarding this aesthetic though though, or aligning myself to any form of Flicker family). Take for example one of my favourite Flicker groups started by a friend of mine who tends to enjoy this aesthetic. Many images from this group illustrate Murray's point.

'Mark watching fireworks and the sometimes beautiful limitations of digital photography.' From the DigitalFaun Flicker Group.

Murray quotes Manovich at the end of her article, "digital photography has not revolutionized photography...it has significantly altered our relationship to the practice of photography (when coupled with networking software)" (161). I agree exactly with this point. Photography is continuing along a long line of improving technology and practices and any panic about the loss of the real is rooted in incorrect notions of the photographic real. However, what is changing is our relationship to the image. A slower world of images bound up with the real, preservation and death has shifted to a more rapid world of constant interaction and transformation, depending of the presentness and newness of each image. Photographers can pull out of a huge pool of resources, viewing work from photographers from any area across the globe they desire, discussing work with those that in the past, would have been impossible. All images, wether shot on large format or a mobile phone, are viewed, criticized and discussed on an equal plane.

Moving onto Evan's text. Wow, what a seriously interesting and relevant piece. Reading this article makes me extremely excited to be apart of the generation he is discussing, but also extremely frustrated. Evans enthusiastically discusses the potentials the internet offers photographers, claiming if we want an audience, the internet is the place to be. He feels however, that photographers have not taken advantage of all the internet has to offer, "imagine Andy Warhol and the internet. (48) One replier argues, however, that the time for internet photography is simply not right. He claims that "there is very little at stake"(49) by posting work on line as the internet is a democratic space. This is a really interesting point. Anyone can be a photographer, once they have a digital camera and an internet connection. The can receive thousands of hits by falling into one of the Flicker categories discussed above, but where does the line between significant and meaningless fall? There are not established critics on the internet. However, photo critiquing via blogging is slowly becoming popular. I have my own blog, where I post work by others and discuss it, sometimes in relation to texts or photographs from the traditional photographic timeline. I highly enjoy engaging with work posted online and looking at it from a serious critical stand point. I don't think its wise to view work on the web as completely cut off from the tangible art world. Obviously my blog isn't really of any importance, more of an entertaining hobby, but think what could be possible if MOMA or the MOCP brought out a blog of this type? It would be really fascinating if these institutions, the arenas Evans sees the internet as perhaps competing with, surfed the web on sites such as Flicker and Tumblr for emerging talent and gave them a platform on a site with critical engagement from established critics. If I was John Szarkowski, people would pay a lot more attention to what I had to say about their work.

Evans touches upon something that I have been thinking about for quite sometime and I'm so relieved someone finally wrote about it and pointed out the significance. Fried hails artists who make work "for the wall" as the new revolutionary masters. What he ignores completely, to my annoyance, is that people are now also making work for the web. As horrifying as these may seem to some, I find it incredible that a whole section of photography is emerging quietly below the surface of polished, exclusive institutions of the art gallery. Its an arena where the art dealer choke hold has no power. In this vein, I can completely understand why he sees the internet as "free." The days of needing to be accepted into a bourgeois gallery to be noticed are over (take for example my presentation topic, Sandy Kim, who now has has tangible work in the form of 500 books for sale and an exhibition under her belt, thanks to the internet).

vs

However, it is important that Evans mentions that not all work is suited for the internet and vice versa. His example of Orzoco vs Crewdson was a good illustration. Crewdson's work is one hundred percent made for the wall. All its glorious detail and production value is dulled and murdered by the internet and its rather upsetting. However, as work like Orzoco's works adequately. Some work is suited for the internet, some is not. We are now in the age of the work of art in the age of digital reproduction. The same concerns apply, I don't see how this problem is any different to choosing wether to shoot with an 8x10 or an iPhone. Artists have the advantage of producing beautiful prints for the wall and work for the web. Why not do both? Why choose? I take advantage of both, big time. I make work for my own personal pleasure that I enjoy posting online and will probably form a book out of someday. I also make work where first and foremost I am considering how it will look printed and framed. Some of my work looks awful online, so I don't post it, some of my work looks awful printed, so I don't printed. I am an avid collector of photography books and the library is one of my favourite places to be. I would never give this up. I like to get up close to a print and inspect how the photographer chose to format their book, I like to feel the print on the page, I like to sit in the gallery and soak up the marvel of the exquisite print quality of an artist's work. However, I can also sit for hours and hours searching through flicker or tumblr as the author described and experience a completely different, but just as wonderful way of viewing art. I can see the power of the internet as a research tool, but this doesn't mean I push a side tangible art work. Why anyone would see this as a disadvantage, or feel they have to side with one school, baffles me. The internet obviously has its disadvantages, but if used correctly, it can empower and promote and artist wonderfully which can lead to exhibitions and commissions.

The last text was by Lev Manovich. Luckily I saw his lecture.. This bloke has a pretty legitimate pink watch which I'm going to assume is similar to batman's utility belt or that device in Men In Black that wipes your memory. He also has a cool accent, therefore he is obviously a genius. Seriously, though. Manovich has some very forward and practical ideas about the internet and its power to organize images in relation to history. His concepts seem simple but are incredibly complex, imagining putting them into practice gives you quite the headache. His text was just as intriguing as his lecture. Manovich raises many important questions for photography in the internet era. He claims we have moved from "media to social media" (319). He discusses how the user now largely adds content to the sphere, rather than consuming content created by a higher source. However, he notes the this is simply a system of recycling of original higher source media. To explain this, he discusses de Certeau's theory of everyday life and Strageties versus tactics. What has changed is that media/commodification now depends on the habits of consumers, which really depends on what is pushed on them by the media, so both parties feed off one another. Manovich applies this to the internet, via sites such as Facebook and Flickr. He also discusses how this type of media has led to new types of conversations, for example, he discuses YouTube and how one video may be responded to with another video. Allow me to give an example (Nothing to do with art..but amazing).

And the response to this video:

What is most interesting is his comparison of conversations held through modern art, such as Jasper Johns reacting to abstract expressionism, or Fried's attack on Minimalism in "Art and Object-hood" and how this is a continuation of such practices. He notes that obviously few of these conversations have the same theoretical groundings, but do aid the shaping of professionally based media, such as video games, film companies and musicians. Manovich asks a very important question. Is art after web 2.0 still possible? I was relieved to see that wrote, "on one level, this question is meaningless" (329). The internet provides many advantages and many disadvantages for artists. As Manovich mentions, artists now now have to compete with millions of other photographers posting online, as well as popular online culture (the avoidance of people "stumbling upon" their site by accident as Evan's commenter mentions). Simultaneously, online communities strengthen are and bring artists together in a way before unimaginable. What Manovich is more concerned with, is the dynamics of Web 2.0 itself, "its constant innovation, its energy and its unpredictability" (331).

Note: Blogger seems to enjoy randomly deleting and reformatting my posts for kicks, whilst I'm not online, so, apologies for any broken links/images.

Note: Blogger seems to enjoy randomly deleting and reformatting my posts for kicks, whilst I'm not online, so, apologies for any broken links/images.

No comments:

Post a Comment