In ‘An Archival Impulse’, Foster is careful to distinguish that work he is discussing is less interested in “absolute origins” and more with “unfulfilled beginnings or incomplete projects, that might offer points of departure again.” (144) He also notes that this work has departed from mourning or criticizing the museum as a failed platform for artistic display, but rather suggests an alternative kind of ordering, “within the museum and without” (145). What is interesting about this kind of work is that it invites the spectator think about how art is made, why it is made in a certain, how it is popularized, etc. It asks us to consider the politics, control, construction and destruction of public archives, also. Instead of presenting a piece in a way that closes off further questioning, it asks questions. As Foster notes, it “ramifies like a weed or a rhizome” (145). He acknowledges the absurdity and paranoia associated with such work and how it can sometimes seem “tendentious, even preposterous” (145) to attempt to replicate the archive. He ask, is it obscene, to attempt to recuperate failed visions of society and art into an alternative kind of social relations, an attempt to reassemble a failed dream of utopia? I don’t think so. I think this kind of interrogation is necessary and has always been a practice I have admired. I think the shift from “excavation sites” towards “construction sites” is essential for artistic practice to evolve.

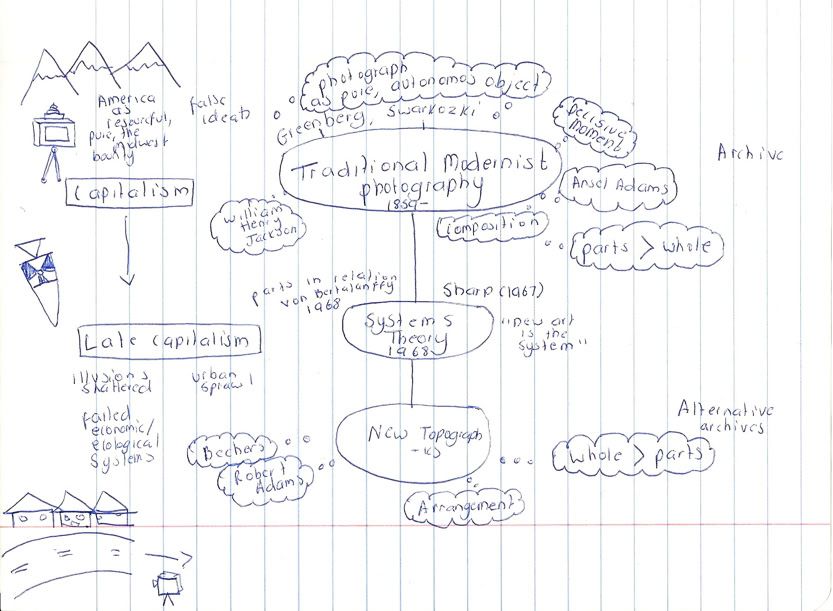

This type of art’s main concern (Minimalism, Earthworks, Conceptualists, etc.) was to be more interactive with the world it resides within. Foster-Rice discusses that what was revealed by this method of thinking, was that notions of art were transforming and artists were aware of and challenging past and current systems. Consequently, the emphasis of object making had shifted to an interest in systematically made art. The materials became of lesser importance, whilst the concept, the system became key. The photographs from the Man-Altered Landscapes become something different in this sense, not simply a muted display of minimalist lines, repetitive images and shapes without purpose other than aesthetic, but rather a challenge of the mid-century Modernist aesthetic using a systematic approach.

Instead of..

In fact, as Foster-Rice explains, this was one of the most pressing areas explored in this Systems approach, that of the human-altered landscape. Artists such as Tony Smith and Lewis Baltz began to criticize the malfunction of new structures of mass suburbanization and the expansion of roads into super highways. Despite Jenk’s overlooking or perhaps disinterest in this issue, those in the larger ‘New Topographics’ sphere were addressing the disastrous implications of these growths, as Foster-Rice notes, what Frederic Jameson called the “cultural logic of Capitalism.” To overlook this would be to deny an important section of art history. As Foster-Rice claims, this exhibition has more to do with Late-Capitalism, rather than a universal alteration of the landscape driven by human development. The images Foster-Rice discusses display various concerns about the irreversible effects of such developments on the natural landscape and the pathetic and dysfunctional attempts to control the resulting waste it produced. These images stand in contrast to those created by previous landscape “masters” (sorry, I really detest that word) who made images to promote the strength and beauty of America in all its infinite resourcefulness. As Foster-Rice notes, the advent of the atomic bomb and its looming possibilities shook such perceptions and shaped the ambivalent anxieties inherent in the photographs of the New Topographics. Foster-Rice argues that what became of central importance at that time, as pressed by Valie Export was to avoid separating the art object from lived experience and rather to see art “as an analogue for experience”, a notion in which photography played a central role.

Foster-Rice claims the New Topographics addressed these issues through three central systems-based strategies: an emphasis on serial images, procedure over aesthetic composition and the creation of images whose arrangement was emblematic of the system as a whole. The work of Adams and the Bechers exemplify the use of serial images, employing linear progression and grid systems. Foster-Rice notes the importance of this practice in focusing the audience’s attention on the project as a whole, rather then as individual photographs. Foster-Rice explains that the New Topographics dismissed Formalism as championed by Szarkowski and embraced a procedural method of creating photographs; in other words “process takes place in the conceptual domain” (64). This work did not depend on the whimsical, fleeting moment, but rather a rigorously planned formula. The work privileged arrangement over composition, attempting to approach the object as a whole, rather than focusing on specific parts, as, for example, a Winogrand portrait would. As skeptic as I am about any possibility of passivity of frame, these artists came as close as possible with this technique. Foster-Rice also discusses the ability of this work to present “Whole Systems” (66), reminiscent of Smith’s quote about the overwhelming lack of reference points in Late-Capitalist society, which was aided by the mode of presentation, which mocked this society, repetitive, lifeless, practically identical.

Finally, Foster-Rice notes that this exhibition can be considered within George Baker’s “Expanded Field of Photography”, building on Krauss’s original essay. He notes that this work “clarifies and reconfigures the possibilities afforded by the opposition of “art” and “document” that tended to document much photographic discourse” (69). The Systems Artist inverted the notion of “not document,” “not art” and created what was both art and document.

Re-reading the Foster text and reading Foster-Rice’s text was really interesting for this assignment, as I have always bee interested in notion of the archive in art and also the New Topographics but struggled to grasp the driving forces behind this work. I think Foster’s text is of great importance as the archive is something that effects historical discourse more than many would consider and for artists to take on such a role is something I would be delighted to witness more of. Foster-Rice’s text achieved its goal of altering how the viewer considers this work, as considering the Systems approach actually explained this work to me more than I had been aware of before. I didn’t know anything about the General System Theory and I hadn’t connected up the ties to Late-Capitalism in this work, so I am grateful to have read this and it will certainly be useful in further studies of this work.

'Northerns Sunsets #2'

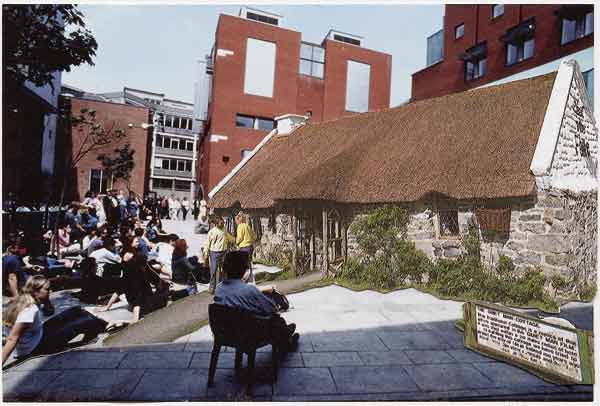

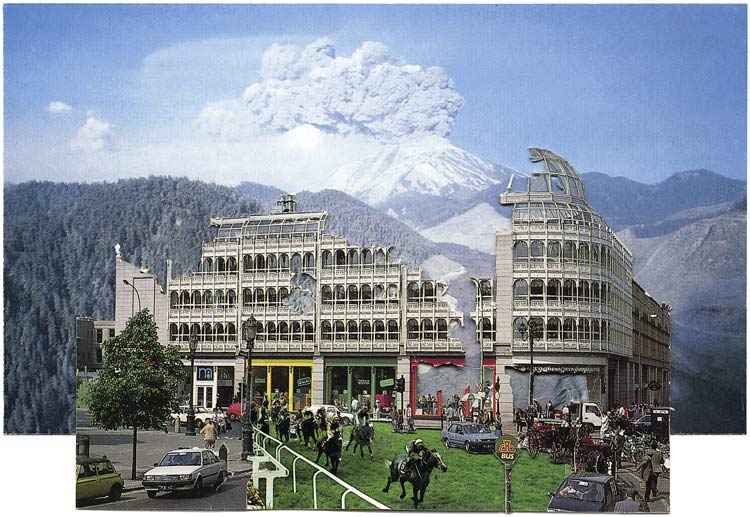

When I consider the Procedural Method of working and the Archive I thought of two examples immediately. Firstly, mostly in connection to the artist as Archivist, Irish artist Sean Hillen creates photomontages, which critically comment on the Northern Irish conflict (English occupation of Northern Ireland and the internal conflict between Republicans and Loyalists). Hillen grew up in Newry, which lies on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic and therefore witnessed much of the conflict first hand. Hillen’s work creates an alternative archive from many of the photographs available in Ireland’s main archival centre, the National Archive. His work comprises of his own photographs, and found images. He employs lengthy, often humorous and satirical titles to enforce his opinion on the situation. Hillen’s later work critically comments on post “Celtic Tiger” (short economic boom, followed by a massive and messy crash) Ireland. I thought this work was relevant to mention in relation to the archives discussed by Foster. As Foster notes, the goal of this work is to “offer points of departure again,” which it certainly does.

'The Quiet Man Cottage in Meeting House Square, Temple Bar, Dublin'

'Horse Racing Near the Ruins of Stephen's Green'

As for Procedural Methods, I thought of the artist Roni Horn and her piece ‘You Are The Weather.’ Interestingly, Horn’s origins lay in Minimalism, but she eventually began making Conceptual based work. In Horn’s ‘You Are the Weather’, she photographed a young woman in Iceland (you can see a short video about the work, here: http://www.pbs.org/art21/artists/horn/clip2.html#) standing in a body of water. Horn used the same vantage point in every single image and, similarly to the Bechers, the only difference in each image is a slight change of expression on the young woman’s face, as in the water towers photographed by the New Topographics couple. Perhaps one could argue, because Horn is photographing a human, rather than a lifeless water tower, that she had to have influenced the subject. What I am more interested in is the similarity of System of framing and presentation used, the notion of repetition, continuous framing, consistent printing, etc. How the images are displayed conveys an ever so subtle sense of emotional change that could only be achieved by employing this procedural system. When viewing the images in this manner, we begin to notice a slight stress in the models eyes, or an absence, or in some a relaxation. The work may not be as strictly precise as the Bechers, but, I think this work is really interesting to consider under the idea of Procedural methods of art making and systems as it shows how it can employed successfully outside of landscape based work.

No comments:

Post a Comment