In Swarkowski’s article, he explains how photography exploded into the world, disturbing the second reality created by painting. Photography added a new layer of vision to art and planted what Swarkowski calls “remembered images” in our minds, which fundamentally saturated our mental images of the world. He explains, with a strange similarity to today’s concerns, (his use of the word “stream” of images) how photography became the “everyman’s” too, a less precious medium than painting. Swarkowski outlines how photography evolved through various experiments, accidents and systems, he calls “section views through the body of photographic tradition” (3). In his first section “The Thing Itself,” Swarkowski describes that the condition of the 19th Century was not to remember the moment itself, but the photograph of the moment. Obviously, as he acknowledges, this creates complex problems. Even, if as Hawthorne claimed, the photograph outshone the painting in its ability to unlock the secrets of the world, how can we trust its image?

Swarkowski continues by expressing his view that photography is a failed tool to convey narrative. Its rather curious, reading this article from 1966 to read Swarkowski’s description of Robinson and Rejilander’s composited negatives (1857) as “pretensions failures” in the eyes of the art world, received poorly in comparison to how work such as this is received today. From the image above, we can see that these composites are similar to the work of contemporary photographers Fried categorizes in his “new regime.” Robinson and Rejilander are the original Wall and Crewdson, yet in their time, their work was criticized. Why such work viewed differently today? Is it that the work of Wall, etc, now has the support of cinema to hoist these images into acceptable art? Is it the distance from its shaky past as painting’s competitor? Is it that the moments Wall attempts to recreate a “near documentary” rather than “near painting?” I think this is really interesting to consider. As Swarkowski, the general consensus during his time was that if you need text, your photographs are not good enough, if you are mocking painting; you are disregarding photography’s true power to capture the “decisive moment.” I think the dominance of advertising and television along with of course the internet, in more recent times has again shifted our view and allowed these type of images to be, not only acceptable, but expected. In fact I would go as far to say, as Fried so aggressively suggests, if you’re not photographing “for the wall” you will have a hard time being recognized as a professional photographer.

Marcel Duchamp 'Nude Descending a Staircase.'

Photography is in a very different place now and I wish Swarkowski could write this article again, in 2010. I would love to hear his views of Fried’s claims. What influenced the work and the structures then was, as he mentions, other photographers and painting (as he mentions, Duchamp’s motion paintings which merged Cubism and Futurism to create a radical study of stop motion) and positivistic studies of the world (Muybridge’s galloping horses). The world has changed an insane amount since then, so much so that Swarkowski’s terms need to be expanded. The decisive moment is no longer dominant. Photographers have slowed down and are realizing their power to construct stories through methods used by Wall and Crewdson. In the 60’s, the “real” moment was privileged; in 2010 the recreation of the real is dominant. Simply ask the one classroom of students at Columbia and I am willing to bet half are working with recreated or fictional images rather than snapshots, students don’t wander the streets seeking out the decisive moment, they don’t have time for that. Photography was not such a widespread practice in terms of degree programs in the 60’s and I think this accounts for the shift also. Working in an institution with deadlines and rules hinders intuitive and impulsive work. The Jeff Wall’s of the world are taking over whilst the Henri Cartier Bressons are suffering. Swarkowski’s view is that photographs cannot tell stories, that they are simply images that portray a certain moment in time. He dismisses any attempt of the image to convey a narrative, through text or awesome (I mean this in non “dude” like terms..) composites. Interestingly, he fails to mentions what Barthes calls Syntax as an attempt at image narrative or photo-journalistic systems of the “three-picture story.” Personally, I think photographs have thousands of stories to tell, these stories are not necessary the truth, they are not necessarily real, but they speak to us. Photographs are always rooted in text and rooted in the real and therefore human beings will always bring their active minds to an image and perceive some sense of the world, some form of account. I think what Swarkowski is more concerned with is photography’s failed attempts at story telling, its imitation of painting, it overbearing theatrical elements, which seem to embarrass him. Swarkowski seems to think documentary images are more “real” and acceptable as they are acknowledging their inability to tell a story, but embracing their ability to freeze a moment in time and transform it into a solitary representation.

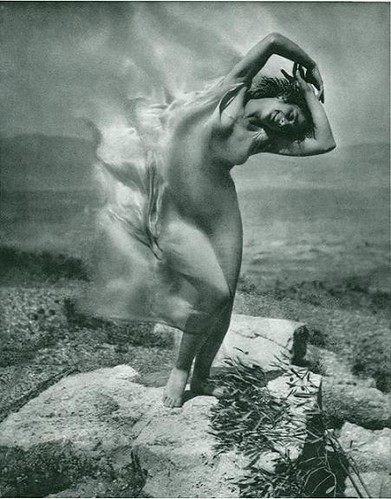

Edward Steichan, 'Acropolis at Athens.'

Clement Greenberg, however, believes that images can tell a story, but in turn, fail as pictures. Greenberg’s article is harsh in its criticisms and brushes aside any photography that falls outside of his snobbish view of art. Greenberg’s privileging of painting and sculpture is clear as he seems to only discuss work that relates to it in some way, then takes pleasure in calling its attempt at measuring up as “disastrous” (4). He pokes fun at experimental photography claiming it is a reaction to the purely formal or abstract. His ideal of the successful photograph is clear, he wants photography to be art and simply art, not a story telling device. I imagine his views are not entirely but somewhat similar to Fried’s (obviously Fried’s view is in a different era) and that he desires absorptive, non-theatrical art. For example, he discusses Steichen’s ‘Acropolis at Athens’ as a failure due to the woman’s ruination of the picture by lifting her arms gayly, disrupting the possible “artiness” of the picture. (I am reminded of Fried’s discussion of a picture where the artist’s wife was engaging the subject and therefore disallowing absorption and the problems this caused). By gesturing as such, she creates a tension between herself and the stone bust, asking the viewer to compare the two, with her more successful as the living object. In other words, she creates a theatrical element; she is attempting to tell a story and therefore, the picture fails.

Greenberg continues in his harsh and almost dismissive tone. He informs the reader that photographer’s should be thankful we don’t have the same concerns of sculptors and painters (as “real” artists, ladies and gentlemen). He can’t resist criticizing even “one of the best photographers of our day” (4), Cartier-Bresson for being too esoteric in his conquests as a street photographer. He praises WeeGee’s daring yet belittles him as a tabloid photographer and calls him “demotic” (4). However, it is Greenberg’s belief that the demotic is more apt in photography, the tool of the eveyman. I’m not really a huge fan of this article as Greenberg discusses four photographers and vaguely pertains to some experimental techniques with a tone that, frankly is rather offensive to me as a photographer (and believe me, I know how to criticize and recognize the failings of my own medium) and seems to think he knows the medium inside out. I would be interested in reading more of his writing on photography, because at least from this article, he seems to consider himself quite the expert, yet doesn’t really offer much. He fails to acknowledge that he is accounting for a very small part of photography in his article and seems to look down on the medium as art’s annoying little sibling. Basically, Greenberg sees photography that is too theatrical in its story telling as failures as art. He privileges the silent, contemplative, absorptive image and basically suggests photographers stay away from anything more complicated than that, otherwise we will fail.

Anna Gaskell, 'Untitled #59 (by proxy)'

Miles Coolidge, 'Safetyville'

Charlotte Cotton brings a more contemporary view to this matter of narrative photography. She discusses how this type of photograph is now often called the “tableau” and that this type of work is not mimicking painting, but simply employing the same code of representation. She discusses the work of Jeff Wall and Phillip Lorca di Corcia and notes that this work should not be seen as an attempt to imitate cinema either, nor advertising, nor the novel, but simply as acknowledging these elements as points of reference that can enhance the images’ story telling ability. Cottons also discusses how tableau images, though often referencing, criticizing and paying homage to painting, can also be ambiguous, inviting the viewer to make up his or her own mind about the story. Some images depict subjects with their faces turned away, leading the viewer to grapple only with the surrounding interior and its objects to construe meaning. Other images play directly on fairy tales, legends, historical references or fantasy. Cotton outlines a variety of contemporary artists who use story telling in their images using techniques that differ significantly from Swarkowski’s description. These images are rigorously planned, produced and subtle in their story telling. The images prove that to tell a story, an image does not have to be overly dramatic or obvious, for example, Anna Gaskell’s ‘Untitled #59 (by proxy)’ tells the story of Geneva Jones, a nurse who murdered her patients in a simple yet very effective manner. Miles Cooldige's 'Safteyville', without including people or employing any theatrical elements at all points out the bizarreness of contemporary society. That a model building attempting to create the ultimate safe town was built sheds light on the paranoia and desire for utopia that exists in Western society. These images are examples of how far photography has come since Greenberg's and Swarkowski's time. Their texts were significant and accurate in the context they were written in and certainly the ability of an image to tell a story is still in question. However, the picture-as-story is widely employed in Contemporary art and is continuously proving its ability as narrative. I think the most important thing to remember is that a photograph is always only the point of view of the photographer. Thus, the photograph is their story and it is our job as viewers to interpret a photograph with this in mind.

No comments:

Post a Comment