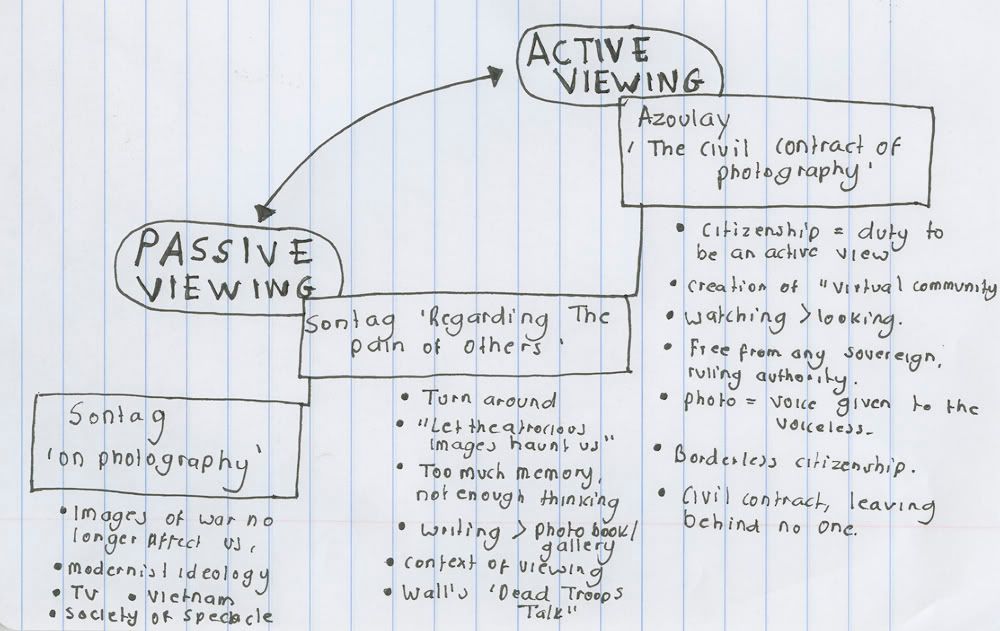

This week we moved on from Fried (though you can never really move on from Fried, can you?) and started a new topic: Photography and/as ethics. To begin, we were to read Susan Sontag's 'Regarding the Pain of Others' and Ariella Azoulay's 'The Civil Contract of Photography'. Both books differ significantly from Fried's writing, particularly Azoulay's. Sontag's text revisits her influential 'On Photography', revising her argument that the images of war and suffering were defunct due to an over saturation of images of horror. Sontag turns her point of view around completely and is characteristically straight forward in expressing this, "let the atrocious images haunt us. Even if they are only tokens, and cannot possibly encompass most of the reality to which they prefer" (115). Previously, Sontag criticised photographs such as Nick Ut's photograph of the Napalm victims in Vietnam for simply showing unnecessary suffering, but Sontag has obviously changed her point of view. I wonder what convinced Sontag to change her tune. Perhaps, a factor in this is that the images Sontag was observing in 'On Photography' were of moments passed, done with, even if they were not that long ago. Opinions changed after Vietnam, war was seen through different eyes. For the first time violent images displaying the reality of war were illuminated through the televisions sets of Americans. Dead children staring out of the photo frame urged the American population to accept the truth. Artists addressed the situation, students protested and died for the cause. Everything changed. Not to say that war became any less of an American tradition, but a fraction of the horror was revealed. When the dust settled, Sontag looked back and with tired eyes and criticised these images. To the best of my knowledge, 'Regarding The Pain of Others' was written in response to the photographs released from Abu Ghraib. It seems to me that Sontag realised it is much easier to sit back, when time has passed and distance oneself from images of suffering and say "do I really need to see that?" It is as if the events of 9/11 and the disastrous mess America got itself into following this reignited something in Sontag that she had forgotten. Of course we need to see these images. This is the only voice these victims have. The photograph, the trace of the event, the confirmation that this happened, it may be the only chance these people have be be placed in history and not forever silenced and forgotten, like so many before and after. I would like to note that Azoulay's text was written in 2008, whilst Sontag's was written in 2003. Why Azoulay ignores Sontag's new text (at least in the amount we have read so far) is intriguing to me. She criticises Sontag's writing on war images but does not note that she has since revised her arguments. Despite this, it is obvious from Azoulay's gripping text that she knows what Sontag had forgotten and has never once lost sight of it. A word you will not find extensively in either of these articles is "art", "anti-theatricality" or "absorption". Unlike Fried, neither author's are interested the placement of photographs into modernist timeline, connecting work to painting and fine art. Neither author's are interested in theatricality vs anti-theatricality (although their are some connections), nor object-hood and absorption. What these authors are interested in is the photograph as a public space for debate, a tool for reporting the situation of a community or person, an incentive for social change and political discourse.

This week we moved on from Fried (though you can never really move on from Fried, can you?) and started a new topic: Photography and/as ethics. To begin, we were to read Susan Sontag's 'Regarding the Pain of Others' and Ariella Azoulay's 'The Civil Contract of Photography'. Both books differ significantly from Fried's writing, particularly Azoulay's. Sontag's text revisits her influential 'On Photography', revising her argument that the images of war and suffering were defunct due to an over saturation of images of horror. Sontag turns her point of view around completely and is characteristically straight forward in expressing this, "let the atrocious images haunt us. Even if they are only tokens, and cannot possibly encompass most of the reality to which they prefer" (115). Previously, Sontag criticised photographs such as Nick Ut's photograph of the Napalm victims in Vietnam for simply showing unnecessary suffering, but Sontag has obviously changed her point of view. I wonder what convinced Sontag to change her tune. Perhaps, a factor in this is that the images Sontag was observing in 'On Photography' were of moments passed, done with, even if they were not that long ago. Opinions changed after Vietnam, war was seen through different eyes. For the first time violent images displaying the reality of war were illuminated through the televisions sets of Americans. Dead children staring out of the photo frame urged the American population to accept the truth. Artists addressed the situation, students protested and died for the cause. Everything changed. Not to say that war became any less of an American tradition, but a fraction of the horror was revealed. When the dust settled, Sontag looked back and with tired eyes and criticised these images. To the best of my knowledge, 'Regarding The Pain of Others' was written in response to the photographs released from Abu Ghraib. It seems to me that Sontag realised it is much easier to sit back, when time has passed and distance oneself from images of suffering and say "do I really need to see that?" It is as if the events of 9/11 and the disastrous mess America got itself into following this reignited something in Sontag that she had forgotten. Of course we need to see these images. This is the only voice these victims have. The photograph, the trace of the event, the confirmation that this happened, it may be the only chance these people have be be placed in history and not forever silenced and forgotten, like so many before and after. I would like to note that Azoulay's text was written in 2008, whilst Sontag's was written in 2003. Why Azoulay ignores Sontag's new text (at least in the amount we have read so far) is intriguing to me. She criticises Sontag's writing on war images but does not note that she has since revised her arguments. Despite this, it is obvious from Azoulay's gripping text that she knows what Sontag had forgotten and has never once lost sight of it. A word you will not find extensively in either of these articles is "art", "anti-theatricality" or "absorption". Unlike Fried, neither author's are interested the placement of photographs into modernist timeline, connecting work to painting and fine art. Neither author's are interested in theatricality vs anti-theatricality (although their are some connections), nor object-hood and absorption. What these authors are interested in is the photograph as a public space for debate, a tool for reporting the situation of a community or person, an incentive for social change and political discourse.At the beginning of Sontag's book, she writes "I wrote, photographs shrivel sympathy. Is this true? I thought it was when I wrote it. I'm not so sure now" (105). Sontag notes that the argument that "modern life consists of a diet of horrors...to which we become gradually habituated" is a "founding idea of the critique of modernity" (107). However, Sontag points out the flaw in this kind of thinking. Firstly, it assumes that "everyone is a spectator. It suggests, perversely, unseriously, that there is no real suffering in the world" (110). Secondly, this reaction only concerns two groups of people, cynics who have been lucky enough not to experience war and the war weary who are enduring being photographed. What Sontag considers is those this type of thinking excludes. Sontag also discusses the subject of the photograph (precisely what Azoulay accuses her of ignoring). She talks about victims and how they are interested in the "representation of their own sufferings" and how they want their suffering "to be seen as unique" (112). To support this, she discusses the exhibition by Paul Lowe, which displayed images of Sarajevans and Somalians, both suffering the impact of war. Sontag discusses how it was seen as "intolerable" to have two separate people's suffering displayed in one exhibition. How valid is this point? Obviously the reactions of the Sarajevans was twinged with racism, so does this deal specifically with how the world want their suffering to be portrayed? Is Sontag suggesting that images of suffering are fighting for the attention of those who can aid the situation? Unfortunately, I think it is the sad truth that images of suffering must compete for attention, if pity, empathy or practical aid is the desired result.

Nick Ut, 'Napalm Girl'.

Sontag follows with another important point, that news and photography about war is now disseminated does not mean it effects a person's sense of moral justice any less. Sontag also notes something that we often forget: a photograph is not an easy fix of conscience. A photograph "cannot repair our ignorance about the history and causes of such suffering it picks out and frames" (117). The basis of all suffering is ignorance, silence, denial. Nobody speaks out, nobody is saved. A photograph cannot cure this atrocity, but it can shed light on it. A photograph can provide a voice where there is nothing but deafening silence, a light when there is only darkness. I will discuss this further when I write about Azoulay's texts. Sontag moves on to discuss the action of looking at a photograph of suffering and what this implies. She describes that it has been seen as morally wrong to gaze upon the suffering of others, but only because of the context of the viewing. I think this is a very valid point. Something about passing by an image of extreme pain or suffering in a gallery (if, perhaps, it is a class outing or group visit, where one cannot be "absorbed" (oh dear) in its message) seems disrespectful. But, as Sontag notes, "there is no way to guarantee reverential conditions in which to look at these pictures and be fully responsive to them" (120). Of course there isn't. There has been much written on this, in various areas of photography. Does this, however, mean we should give up on putting political (or artistic) messages out into the world, because we are afraid of them being misread? I would say, absolutely not. As Azoulay will note in the next reading, the point of these types of images is to create a "virtual community" (22) a call for a group of unknown supporters. Sontag, however, argues that these images are susceptible to failure in both the context of a gallery and a book, as a book can be closed and the images forgotten. "The strong emotion will become a transient one" (121), she remarks.

So, if there is possibility of failure in both the gallery and the photo book, what is the alternative? Sontag claims "a narrative seems likely to be more effective than an image" (122). Sontag believe a narrative, that requires more intimate time to complete, will have more of a lasting effect. I can completely understand what Sontag means by this. Books do stay with a person. However, a narrative is less accessible. Sadly, people are reading less and less, especially in the category of war. As Sontag previously mentioned, we are consumers and we are weary. I think what it takes is active viewing, making it ones responsibility to be involved in the political, both through photography and literature. Otherwise, it is all too easy to ignore. She also mentions Walls 'Dead Troops Talk', as we have previously discussed, as an example of the perfect contemporary war photograph. As Sontag discusses, the troops ignore our gaze as we "can't understand, can't imagine" (125).

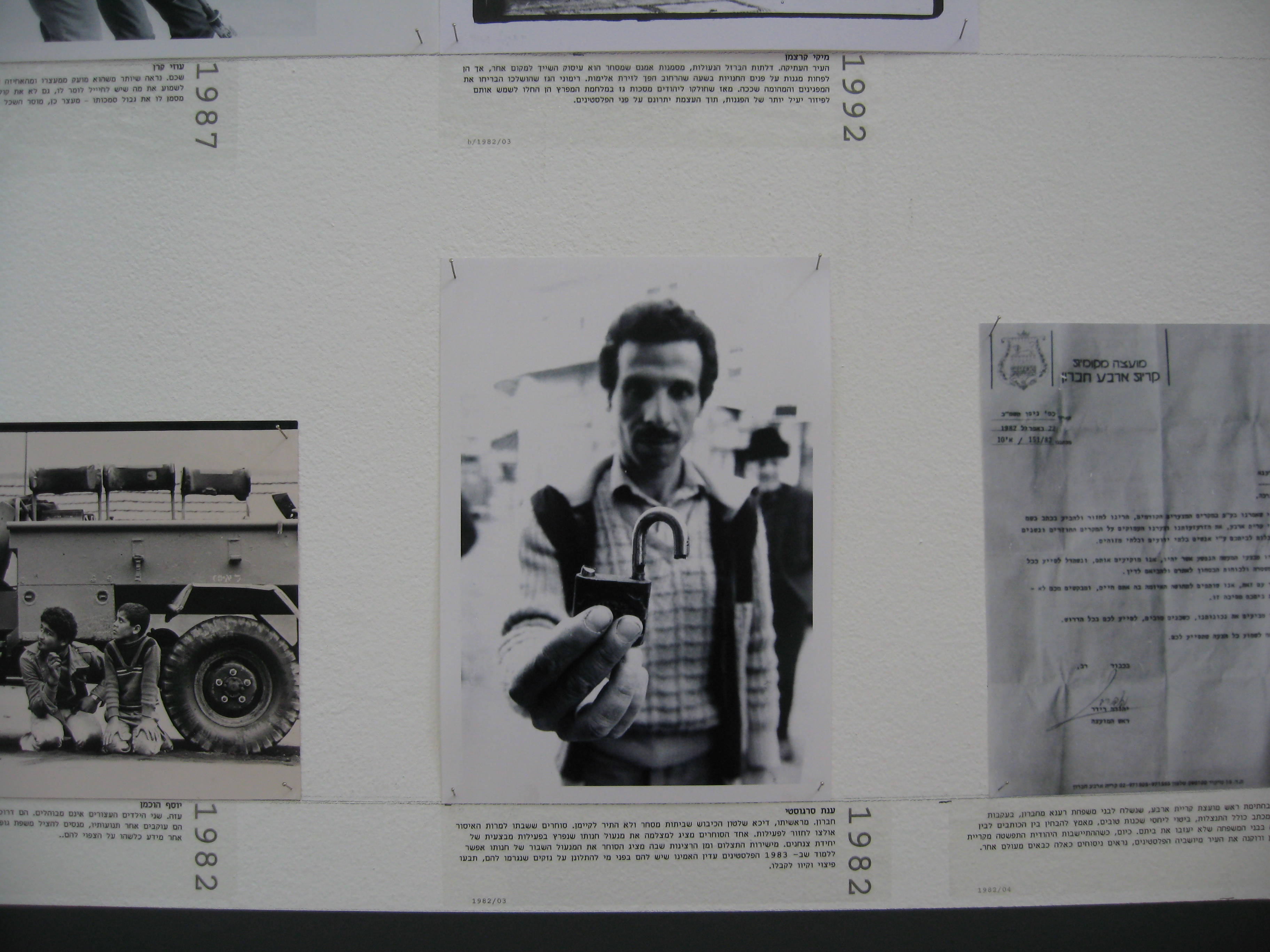

Anat Saragusti, 'Hebron, 1982'.

However, Ariella Azoulay believes that successful images of suffering are looking for anything but sympathy or empathy, they are looking for recognition, validity, seeking justice, angrily confronting the world and stating their status as a victim of something utterly unacceptable. This is why I personally am not moved by Wall's photograph. It says nothing to me other than, war is mad, cruel, terrifying and wrong. Anyone with a brain in their head can deduce this. The photographs Azoulay discusses, however, say so much more than Wall's piece ever could. Fried sees a picture as either theatrical, putting on a show for an audience, or anti theatrcal, avoiding the audience, or accepting the audience passively. Sontag sees images of suffering as devices to horrify, depress, or as invitations of empathy. Azoulay, however, sees things very differently. Azoulay sums up image fatigue as follows: "they simply stopped looking" (11). Azoulay claims the photographed person is always demanding something, be it a politcal demand or perhaps a small demand of recognition (which could be from photographer or subject). She notes that by photographing, we create a physical space and a contract between subject and ourselves. She discusses the "civil, political space we imagine" (12) as photographers and spectators. Its true, we create a target audience in our head, even if that audience is something or someone we do not know. We envision a space in which we imagine the photograph will be viewed and when viewing, we do the same, we imagine the context we are supposed to view it in. This is an important point as we discover, from the onset, the photograph is creating an imagined space.

In relation to imagined space, Azoulay discusses the power of "planted images" (13). She discusses how images planted in a person's head, by a parent, television, stories, etc, shape a person's growth and personality. She gives the example of her childhood warnings, being warned that someone could follow her home (most likely referencing a Palestinien), that she was constantly in danger, that being independent was not safe, that all around her that weren't of her religion were out to get her. Azoulay discusses how images, real images, helped her rid herself of these false ideals, these images of terror that controlled her young mind. She makes an intriguing point that real photographs are confused for planted photographs. The planted image is something ingrained in our heads, something only the individual can understand, you have them, I have them, images fabricated that frightened us, warned us, (don't talk to strangers, don't walk home alone, etc) shaped our view of the world. But Azoulay argues no one owns a real photograph. She argues, the viewing of a real photograph cannot not simply be deciphered as an exchange between photographer and subject, (the spectrum from which Fried largely discusses work). She sees the photograph a a civil contract which should invoke the viewer to actively engage and respond. Azoulay urges us to stop looking and to start watching. Azoulay privileges watching over looking as the act of looking relates to notions of time, space and movement, rather than simple of moment passed. She urges us to participate in civic skill, reconstructing the the cause and implications of the suffering, rather than exercises of aesthetic appreciation. In other words, Fried's method of unravelling what a photograph contains and even Sontags, is what Azoulay would consider the wrong, or faulty method of reading a photograph. Azoulay calls for us to view ourselves as "civil spectators" (14), seeing our citizenship as a "tool of struggle" or "an obligations to others to struggle against injuries inflicted on those others, citizen and non citizen alike" (14). Azoulay is urging us to be active, politically aware spectators and photographers in a world where disregarding the political image is a widley accepted practice.

The concept of citizenship is central to Azoulay's thesis. She remarks that citizenship "gradually became the prism through which I began observing things" (15). What Azoulay witnessed around her as she progressed in life forced her to think of citizenship in a new way. She realised that not everyone was being treated equal. Two factors were central to this realization, the first, being the Occupation of Palestine by the Israelites and the oppression, terror and suffering this caused her to witness and secondly, the oppression and abuse of women in society. She explains that both sections of society, women and Palestinians were repressed and silenced by the false statuses they were given. Women were seen as full citizens and the Palestinians as "stateless persons". If women are seen as full citizens, it is perceived there is no reason to complain of their problems. As for Palestinians, they are invisible, they do not have a voice, even a pretend one prescribed by the government. Azoulay notes that atrocities towards women, such as rape, are not natural disasters and that the privilege of citizenship is not a natural place in the world. Azoulay sees real problems with these false statuses in society. She also find problems with terms such as "occupation", "Green Line", or "Palestinian State". Azoulay explains that these buzz words, if you will, often heard on the news, only circumscribe one's field of visions. She notes that this kind of tunnel visioned observation adds to the testimony of what Barthes describes as proof that something "was there" (16). Azoulay criticises this kind of observation as it implies that what was photographed was there and is still currently there. Therefore, the photograph is easier to take in as it is "less susceptible to becoming immoral". I think what Azoulay means here, is that focusing on repeated terms or the "presentness" of a photograph cuts off further thought, the thought about what happened before and after the event, where the person is now, if the person received justice or not, what is outside the frame, etc. Words become meaningless, just as pictures do, if uttered out of context too frequently. I can remember hearing the words "Gaza Strip" or "The Troubles" various times as a child and having no idea what they meant. Unexplained photographs, just like unexplained words, steer us away from any understanding of the issue at hand. They sheild us from the issue, convincing us it is something we are not concerned with. Azoulay sees the photograph as a political space and does not believe in the limitations of the document of simply "being there." This is something a critic such as Fried completely ignores in his writing. Azoulay claims her writing of this book is an attempt to "enable the rethinking of the concept and practice of citizenship" (17). Personally, I find Azoulay's mission more compelling and relevant than Fried's could ever be. I think what Fried touches on in his book is something extremely important. Theatricality and anti-theatrically is a very solid formula for viewing photographs. However, is this was infused with ideas such as Azoulays or even Sontag's, Fried's words would be much more applicable and relevant. Where I struggle to understand Fried's words, I find applications for what Azoulay says everywhere (I notice I can make much more sense of the work of female authors, which is an interesting side topic, but that's a whole other discussion).

Southworth and Hawes, 'The Branded Hand of Captain Jonathan Walker'.

"When the photographed persons address me... They cease to appear as stateless or as enemies" (17). With this sentence, Azoulay sums up the power of photography when both photographer, subject and spectator are engaged in civil contract. Take for example the photograph by Anat Saragusti. Azoulay notes that his action of holding up a broken lock, evidence of damage done to his business by Israeli paratroopers, is not a request for sympathy. Rather, his stance is a refusal to accept non citizen status thrust upon him by the state. Azoulay goes onto to describe exactly what is a civil contract to us. She uses the earliest example she can find, a picture of the branded hand of Captain Jonathan Walker, a man condemed as a "slave stealer" after attemtping to liberate a group of slaves. What is interesting about this section is Azoulay's discussion of the "virtual community." Azoulay notes that by releasing this photograph, Walker was attemping to ignite a civil contract. He was seeking out people who understood the injustice he was fighting against. These people did not belong to a particular segment of society or insitution. All that mattered is that they understood the civil contract, as it still exists today, the attempt to create a universal citizenship, an uninterupted voice that is free from the constraints of any dictatorship or sovereign (23). As Azoulay states, her book is foued on a "new ontological understanding of photography" (23), one which includes photographer, subject and spectator and the "unintentional effect of the encounter between all these" (23).

Azoulay put this forward to us in her next paragraph or two:

- Citizenship is "a status, instituion, set of practices" (24).

- We are all governed. Though some are given citizen stauts, some non-citizen. For example, Isreali Jews and Israeli Palestinians.

- However, whoever falls under the umbrella of the term governed is not afforded the luxury of equality of civil rights. Israeli Palestinians are treated as second class citizens even though they are governed. Women are treated as second class citizens even though they are labeled as full citizens and governed.

- Thus, the use of the camera allows for the creation of a politcal space or a common ground for "citizens and non citizens alike".

- Azoulay sees photography and citizenship as very similar. Both should be free of any soveregn power and should be "indifferent to the ties from kinship through class or nation - that seek to link part of the governed to one another and exclude others" (25).

- Azoulay also claims "photographs bear traces of a plurality of political relations".

- Azoulay want the civil contract of photography to create a "borderless citizenship" (26) and sees photographs produced by politically aware citizens as "traces of civic skill"

No comments:

Post a Comment