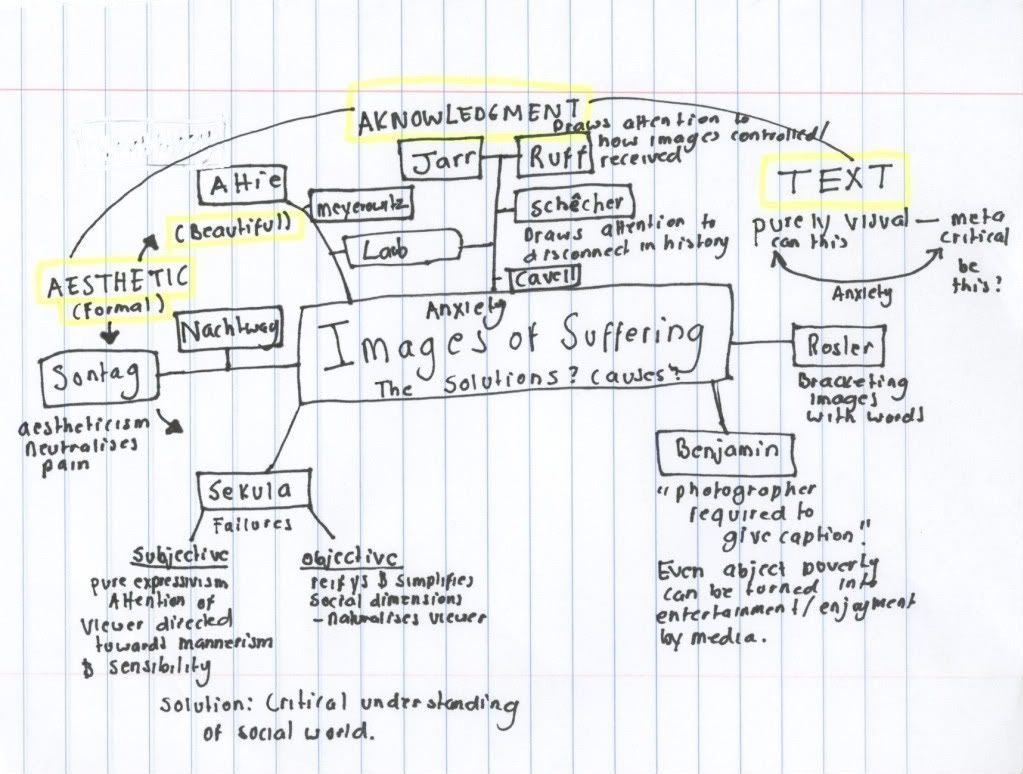

Its my mission to keep this weeks entry short, so hopefully I'll be able to explain my thoughts well. Apologies for being a rambler lads. Our readings for this week were 'Testimony' by Ariella Azoulay and 'Picturing Violence: Aesthetics and the Anxiety of Critique' by Mark Renhardt. The first text is an overview of work by Gillian Laub in relation to Azoulay's Civil Contract, whereas Renhardt's text is a discussion of the various problems and possible solutions surrounding images of suffering.

Azoulay begins by discussing Laub's photograph of a woman on a beach in Jaffa, Tel Aviv. If one is aware of the Israel-Palestinian divide, it is clear that this woman is an Arab, as she wades into the ocean fully clothed, amongst the others at the beach, who we assume are Jews, as they are in swimming attire. As Azoulay mentions, it is obvious after looking at Laub's work that her camera "is sensitive to objects and it frames its subjects relative to them" (97). Azoulay says that these objects are a form of theatricality and performativity "as a mode of routine human existence" (97). This in an interesting point which relates to previous readings of Fried, although of course Azoulay is discussing this act in relation to ongoing, daily life. She discusses a photograph of Azoulay's grandfather, taken en face, which according to her, signifies theatricality. Would Fried agree? Interesting to ponder, but that's not for today's discussion. Azoulay claims the manner in which the spectator can get to know the photographed figure is mediated by the encounter between subject and photographer. She notes that what we find in Laub's photographs are in fact dense differences, rather than hierarchical dichotomies or centers versus margins. Laub is not interested in showing anthropological or ethnographic differences, nor singling out social distinctions. What Laub is interested in is displaying the moment, "when differences between human beings transcend the distinctions of class, identity or belonging" (99). She is interested in the differences that can in fact turn into a fatal distinction when in certain situations. Obviously in this context she is referring to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the widespread violence caused by these very differences.

Azoulay also discusses Laub's frequent use of the word "survivor" and her attempt to frame it outside terms that deal with either the Holocaust or victims of sexual assault. She also mentions how text enriches Laub's pieces. Laub interviews each of her subjects. As Azoulay states "these things assist Laub in suspending the political context of the project she has undertaken, while drawing the spectator gaze the the difficult and complex existential reality of these injured people and the ways in which reality is described by them" (100). Interestingly, Azoulay informs us that Laub attempts to remain apolitical in all her work. Her work is not constructed to convey a symmetrical cycle of violence and revenge, nor a tale of universal suffering. She is not interested in representing a story of one side vs the other, either. However, it is difficult to separate ourselves from the connotations the objects in the photographs suggest. The importance of text comes into play here. Azoulay brings her own theory of the Civil Contract into the discussion when she explains that, "the language of the photographed women and men is that of civilians" who avoid "the language of the blood sucking fantasy of two sides" (101). Azoulay is interested particularly in a quote by one of the young men Laub photographed who claims "the party should make the sacrifices, not its citizens...releasing them from the obligation of pledging their blood to the state. Isn't this the most civil of claims?" (101). Obviously this exemplifies Azoulay's Civil Contract perfectly. Laub's work is a wonderful example of Azoulay's ideas and shows how through a collaboration of subject and photographer, a clear view of a situation and the opinions of those involved can be established.

The author of the second reading, Mark Reinhardt, begins his text discussing the problem of aestheticization in photographs. He notes that when we get the feeling that a photograph is "off" (14) it is generally due to an imbalance of formal or "beautiful" content in relation to a situation of great pain, loss or atrotcity, thus raising uneasy questions about the moral intentions of the photographer. However, Reinhardt discusses how usage of this term is problematic. He claims it is invalid for description as it limits the critics argument . He claims the term raises anxieties which directly link to uncertainties about photography's validity as a form of representation itself. He begins with the example of the infamous Abu Ghraib photographs.

Detainee with staff sergeant Ivan Frederick II in Foreground.

Firstly, Reinhardt dicusses the camera's power as a tool to draw attention to a wrong whilst simultaneously prolonging the suffering we are observing. These photographs confirm this power. As we gaze upon this man with his head hooded, in the stance which immediately connotes christ's suffering, we feel a huge sense of rage, sorrow, injustice, etc. However, by gazing upon him, we are continuing his objectification and humiliation as a victim of torture and sadism. Reinhardt discusses the hesitation of American newspapers to show these pictures, not out of respect for those photographed and what they had been through, but rather, to comply with what is deemed "appropriate" viewing for its readers. He notes that when these photographs were shown, the nudity of the victims was censored, for reader discretion, but their faces wereleft fully visible. However, their was a strict ban on the photographing of, let alone showing, of pictures of American soldiers in any compromised state in this context. Reinhardt discusses the shocking reception of these photographs. These photographs were briefly shown and rapidly removed from public circulation (obviously they are still available online, but no new pictures or reports, which of course are in existence, have emerged). These photographs became symbols of everything that is wrong with the U.S invasion of Iraq, and naturally resulted in a plunge in the war's populaarity world wide. But what real change did they bring about? Obama recently defended his choice to keep the further 2,000 unreleased photographs, some of which to include photographs of rape, sexual abuse, child abuse and abuse of the mentally unstable, saying: "The most direct consequence of releasing them, I believe, would be to inflame anti-American public opinion and to put our troops in greater danger" (UK Telegraph). Obama knows these images have the power to sway public opinion to breaking point and he is not willing to let this happen. Personally, I feel as horrifically damaging as these images are to those who were the victims of such acts, they need to be shown. Blur out the faces, censor the nudity, but show the actions, show the truth. These images have been hidden away as if their release was some kind of hiccup on the part of the U.S/Iraq war P.R campaign. With real time war action photography now highly restricted, these photographs are a hugely important record of how war effects its victims, the Iraqi victims, ironically and disturbingly produced by the torturers themselves. I remember visiting Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Berlin a few years ago, which is now a national memorial site. In the camp, there is a small photo gallery honouring its victims and explaining its history. I remember clearly one of the photographs displayed a Nazi looking towards the camera and smiling as a Jewish prisoner was being tortured in the background. The pure sick enjoyment in his eyes disturbed me deeply and the image was burned into my mind as proof of how people are capable of things that are unimaginable. It frustrates me how people visit these museums, swearing by the oath "Never Again" when the exact same thing is happening as I type this. How are the Abu Ghraib releases different from such photographs? Think of Lawrence Beitler's photograph, 'Lynching of Young Blacks'. (This photograph upsets me too much to be reproduced on here, so if you don't know this one, apologies) These are images of torture and to hide them away is to hide away the issue at hand.

Obviously, the showing of these pictures raises many moral issues, as Sontag so brashly outlined in 'On Photography'. Reinhardt mentions Walter Benjamin's opinion from 'The Author as Producer' that photography has the power to make anything an object available for pleasurable consumption. He also discusses Sontag's belief that by aestheticizing a photograph, we are neutralising what is being shown. As for the photograph of Abu Ghraib, there is nothing beautiful, aesthetic or formal. All I see is raw, shocking truth. But what about other photographs? Take for example, James Nachtway's 'Sudan'.

Obviously, the showing of these pictures raises many moral issues, as Sontag so brashly outlined in 'On Photography'. Reinhardt mentions Walter Benjamin's opinion from 'The Author as Producer' that photography has the power to make anything an object available for pleasurable consumption. He also discusses Sontag's belief that by aestheticizing a photograph, we are neutralising what is being shown. As for the photograph of Abu Ghraib, there is nothing beautiful, aesthetic or formal. All I see is raw, shocking truth. But what about other photographs? Take for example, James Nachtway's 'Sudan'.

Reinhardt mentions the formal satisfactions of this photograph, how the composition draws outr notice, the contrast of lights, the interplay between the cloth and the starving man's body., the sharp diagnol lines. He asks, "are we supposed to be cheered by the triumph of artistry?" (24). He discusses the anxieties this raises as these qualities distract from the issue at hand and therefore seems wrong in some way. Personally, none of these things cross my mind when I see this photograph, I am transfixed on how disgusted and angry I feel in general that people are in this situation in the world. I struggle to understand how this could distract anyone from the tragedy in this photograph. However, perhaps this is down to the number of times I have viewed this photograph, only once or twice and also the context I am viewing it in, in its lesser quality state online. Obviously this is an issue and Reinhardt discusses the use of text to offset this as a possible solution. He cites Sekula, for example as someone who praises artists who "openly bracket their photographs with language" (24), such as Martha Rosler. He also mentions Benjamin's remark, "what we require of the photographer is the ability to give his picture a caption" (24).

Reinhardt moves on to discuss Thomas Ruff's images of the World Trade Centre. This photograph is unnerving as Ruff has pixeletated the image, therefore we are forced to focus on its aesthetic qualities first, then we think about the victims. and the event itself. Reinhardt notes that this very quality is what invites critical engagement "as a kind of meta-critical reflection of the mass-mediated character of disaster.." (26). In other words, Ruff is pointing out that images of political disasters are highly controlled by the Government, as I already discussed above.

Shimon Attie's 'The Writing on the Wall'.

Shimon Attie's 'The Writing on the Wall'.

As Reinhardt mentions, he so far has given little discussion to beauty. He poses the question, "might beauty breed passivity?" and quotes Sontag in claiming "beauty tends to bleach out a moral response to what is shown" (29). He also asks does drawing a line from beautification to aesthetisization identify what makes images of suffering problematic? To discuss this he uses Shimon Attie's 'The Writing on the Wall'. Attie's documented projections are dual purposed Though their intention is to remind us of the lives that were stolen from those who inhabited the Scheunenvietel, the photographs of the projections are strikingly beautiful in form. Instead of becoming a distracting quality, Reinhardt claims "the beauty of the work shapes and intensifies" our invitation to look (30). However, he makes an important point. If Attie had brought this kind of aesthetic technique to pictures of those in the throws of suffering, they would invoke a very different response indeed. This leads me to wonder, is this kind of technique okay only if there is no people actually suffering within to photograph? Is aestheticization a technique destined only for Late Photography, in the context of suffering? Ruff's pieces of the Twin Towers are just as beautiful as Attie's pieces. Why is it that we can happily look at something beautiful that we know is tinged with death and suffering, such as Joel Meyerowitz' photography of Ground Zero, once it is void of people enduring the pain we know existed?

This brings us the the topic of Acknowledgement. In 'On Photography', Sontag writes, "photographs do not explain; they aknowledge" (31). She claims this is not enough. Stanley Cavell, however, think this is the greatest thing we can do for a photograph. Cavell's theory of aknowledgement reminds me of Azoulay's Civil Contract and makes clear that Sontag's view, however valid, is not universally applicable to a large portion of Contemporary photography. Cavell notes that recognition of world issues can come only through aknowledgement and as Reinhardt mentions, "photographs fail morally and politcally when what they invite from a responsive viewer is something less than aknowledgement" (31). He sees this as tied to a picture's visual strategies. Cavell sees a picture such as Sudan as a failure of aknowledgement, as the intention is to display the subject as a human being but instead he is portrayed as an outcast. The photograph simply envokes feelings of outrage (as I mentioned) but nothing more. Its true, I felt this way, but by the time I'd moved onto this paragraph I was no longer thinking of that image. However I will argue against the claim that the viewer is not invited to consider his or her relationship to the subject. I did think of my own position in the world in comparision to the subject's and the various reasons for this. Obviously it didn't do the situation any good, but I would hardly say I saw the man as an outsider, I see him as fellow human being whom I so desperately wish I could help.

Alfredo Jaar's 'The Eyes of Gutete Emerita', which is a piece that uses a radically different technique to that employed by Nachtway. In this piece, Jaar challenges the limitations of photography and representation. He displays what was not shown and ask the viewer to imagine what they would have seen. This is a work that employs text to strengthen is visual impact and at the same time ensures we do not equate the act of watching with the delivering of aid, as perhaps could be construed from Nachtway's piece. This is an interesting piece to discuss when considering the way we are shown images of suffering. Jaar draws attention to the way images of suffering are controlled and censored whilst also highlighting the strength text can add to a piece. Interestingly, he controls the spectator's vision of the piece, forcing them to spend a longer time with the installation then they would perhaps with a photograph on the wall. I'm sure the movement in the piece keeps the viewer anticipating what will happen next, also. Reinhardt wonders if Alan Sekula's observation that images cannot suceed without the agency of letter.

Alan Schechner - 'It's The Real Thing - Self Portrait at Buchenwald.'

Thus, the final photograph Reinhardt discusses is 'It's The Real Thing - Self Portrait at Buchenwald' by Alan Schechner, is a purely visual piece. He notes that this image at first may apprear to be a crude trivialization, or a "failure to recognize the relative weight of two problems.." (36). However, given closer critical attention, Schechner is bravely stating his distance, as a Jew, from this situation. His gleaming can of Diet Coke comes to represent the era he lives in, despite his people's tragic history. Schechner is aknowledging his, well, aknowledegment of this period of history, but is admiting that as a viewer, no matter how hard he tries, he cannot relate. This bring us back to Sontag's argument and her championing of Jeff Wall's 'Dead Troops Talk' piece. Of course he can't relate, but the least he can do is aknowledge and furthermore, enter into a civil cotnract as described by Azoulay, a contract that aknowledges his existence as a citizen who should fulfil his duty to avoid such situations being thrust upon other citizens and non citizens alike in his time.

This brings us the the topic of Acknowledgement. In 'On Photography', Sontag writes, "photographs do not explain; they aknowledge" (31). She claims this is not enough. Stanley Cavell, however, think this is the greatest thing we can do for a photograph. Cavell's theory of aknowledgement reminds me of Azoulay's Civil Contract and makes clear that Sontag's view, however valid, is not universally applicable to a large portion of Contemporary photography. Cavell notes that recognition of world issues can come only through aknowledgement and as Reinhardt mentions, "photographs fail morally and politcally when what they invite from a responsive viewer is something less than aknowledgement" (31). He sees this as tied to a picture's visual strategies. Cavell sees a picture such as Sudan as a failure of aknowledgement, as the intention is to display the subject as a human being but instead he is portrayed as an outcast. The photograph simply envokes feelings of outrage (as I mentioned) but nothing more. Its true, I felt this way, but by the time I'd moved onto this paragraph I was no longer thinking of that image. However I will argue against the claim that the viewer is not invited to consider his or her relationship to the subject. I did think of my own position in the world in comparision to the subject's and the various reasons for this. Obviously it didn't do the situation any good, but I would hardly say I saw the man as an outsider, I see him as fellow human being whom I so desperately wish I could help.

Alan Schechner - 'It's The Real Thing - Self Portrait at Buchenwald.'

Was that shorter than usual? Probably not, I'm sorry. You can't ask me to discuss ethical issues and keep it short and sweet, its my favourite thing to rattle on about. All this discussion on ethical art, if you will, of all these images of suffering, how many of the photographers sell their work and donate the funds to those the photographed? How many use the money raised from their exhibtion to send aid to the victims they claim to care about? I recently attended an exhibition that was orginised to raise awareness and promote dontations, which was uplifting: This show was on in Dublin's main photography gallery (which is hilariously tiny compared to any gallery here, but still great) and donated the funds to Women of Concern. I think this would also constitute as a good example for Azoulay's Civil Contract.

Sources:UK Telegraph.

Iraq Body Count.

Hi Katie

ReplyDeleteThis is Alan Schechner, just to let you know I don't sell any of my work.

A

yurtdışı kargo

ReplyDeleteresimli magnet

instagram takipçi satın al

yurtdışı kargo

sms onay

dijital kartvizit

dijital kartvizit

https://nobetci-eczane.org/

İ84DFA

Nijerya yurtdışı kargo

ReplyDeleteNijer yurtdışı kargo

Nevise yurtdışı kargo

Nepal yurtdışı kargo

Namibya yurtdışı kargo

MYC11