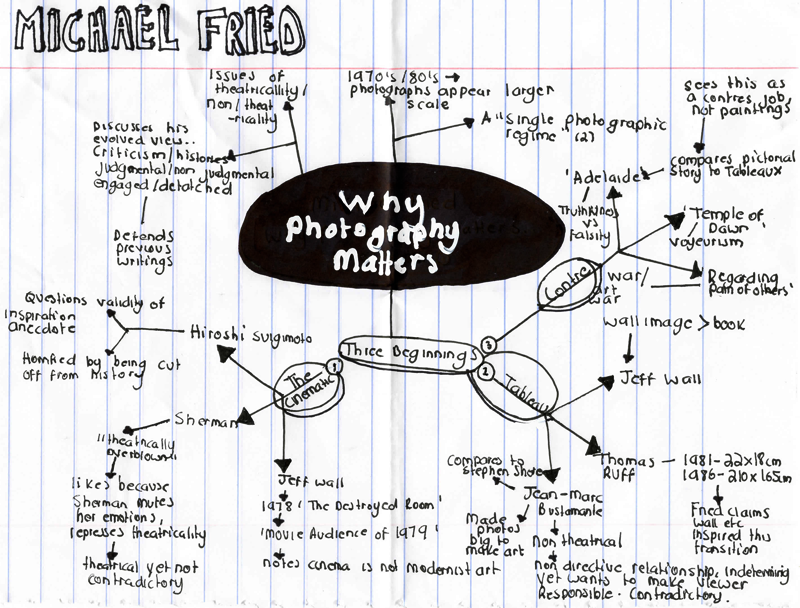

This weeks text for discussion is 'Why Photography Matters As Art As Never before' by Michael Fried. Though at first skeptical of Fried after reading 'Art and Objecthood' and to be frank, rather irritated by his some what elitist view of art, I found he made some interesting points in this later piece. He attempts to redeem himself slightly by revising some of his previous points and re arguing his thesis. However, I think he discredits a lot of art that doesn't fall into what he calls a 'single photographic regime' (20) and has a very tunnel visioned view of what makes photography 'art'.

This weeks text for discussion is 'Why Photography Matters As Art As Never before' by Michael Fried. Though at first skeptical of Fried after reading 'Art and Objecthood' and to be frank, rather irritated by his some what elitist view of art, I found he made some interesting points in this later piece. He attempts to redeem himself slightly by revising some of his previous points and re arguing his thesis. However, I think he discredits a lot of art that doesn't fall into what he calls a 'single photographic regime' (20) and has a very tunnel visioned view of what makes photography 'art'.I'll begin explaining this by discussing Fried's introduction. He outlines his opinion of how photography became elevated into more of a 'serious art' position in the late 1970's/80's onwards. He notes that photography began to be printed at a larger scale, therefore complying to a Pictorialist tradition, thus pleasing Fried, and as we know, he simply loves observing a good old fashioned aesthetically pleasing picture made 'for the wall'. As examples of this type of new photographic 'regime' he mentions photographers such as Welling, Gursky, Struth, the Bechers, Demand, Dijkstra, Hofer and of course, Wall. He notes that he pays particular attention and indeed, he champions his work. This does not surprise me, nor does his anecdote of his shared views of art with Wall. After reading 'The Story of Art According to Jeff Wall' by Sven Lutticken last year, I realised that Wall is obsessed with placing photography into a Modernist tradition and crafting out his own version of history (overlooking anything that doesn't fit into this criteria'). As impressive as 'Mark of Indifference..' by Wall is as a history, it is certainly leaning towards a Modernist elitism and I personally would see him and Fried as two peas in a pod. I am not saying I don't admire Wall's work or his writing, but it is certainly a version of history, similar to Fried's. I will also note that the artists Fried mentions are some of my favourites, their work is impressive and it really is a fascinating transition to see photographs printed at large scale. However, I do not believe in a 'single photographic regime' and this phrase infuriates me. Photography does not have to be at large scale, (mocking and competing with painting) to be impressive. In fact, simple snap shots printed at modest scale have impressed me just as much as a Wall light box piece. Fried notes that he appreciated pictures in this form also, but that do not impress on him as much as a large scale piece could.

So how does Fried approach this gargantuan subject? He splits his history into three beginnings. I found this an interesting approach as it fits into the discussion of Terry Smith's piece last week and his concept of 'antinomies'. Fried sees separate strands of this period of art working in tandem. Interestingly, he also mention that in this text he found himself seeing both sides of the argument (how thoughtful of him!) which he had not done before. He says he found himself 'judgmental/non judgmental, engaged/detached'.. etc (4). Again, this connects with the previous text of discussion. Fried splits the three beginnings into what I see as; the Cinematic, the Tableau and the Contre or story. Fried uses these three strands as a tool to discuss the work of various artists in connection to a single subject, whilst employing his own ideas. I will discuss the three strands in detail.

Firstly he discusses the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall. The common thread in all these works is that they are discussing or representing cinema. Fried gives an anecdotal quote from Suigimoto, in which he explains how this work came to him almost as a vision. Freid questions this 'solitary brilliant intuition' (5) as he find it suspicious that Sherman and Wall were making work concerning the same subjects at the time. I agree this is a valid point, but find it humorous that Fried is so horrified of the thought of an artist working in solitude and not obsessing over placing himself firmly into a history of photography. The works of Wall and Sherman he compares this piece to is Sherman's famous 'Untitled Film Stills' and Wall's 'Movie Audience, 1979.' Fried chooses to discuss Sherman's work because in these photographs, the majority of the characters she plays are mute, passive characters. They dull their emotions (as she said she didn't 'ham it up' (7) as she wanted to play down the theatricality in order to bring into focus questions of the female role in such films. Fried pays attention to these photographs as they nicely exemplify his ideas of 'anti-theatricality'. He notes that he is not impressed by any of Sherman's later projects after her Art Forum series. Again, no surprise, I can't imagine maimed doll figures posed in sexual positions to raise questions about pornography would be Fried's cup of tea. I must say though, I was impressed to observe that Fried noted the contradictions in Sherman's work. It is both theatrical and anti-theatrical and Fried is surprisingly content with this, although as I mentioned above, the work strengthens his arguments nicely.

Firstly he discusses the work of Hiroshi Sugimoto, Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall. The common thread in all these works is that they are discussing or representing cinema. Fried gives an anecdotal quote from Suigimoto, in which he explains how this work came to him almost as a vision. Freid questions this 'solitary brilliant intuition' (5) as he find it suspicious that Sherman and Wall were making work concerning the same subjects at the time. I agree this is a valid point, but find it humorous that Fried is so horrified of the thought of an artist working in solitude and not obsessing over placing himself firmly into a history of photography. The works of Wall and Sherman he compares this piece to is Sherman's famous 'Untitled Film Stills' and Wall's 'Movie Audience, 1979.' Fried chooses to discuss Sherman's work because in these photographs, the majority of the characters she plays are mute, passive characters. They dull their emotions (as she said she didn't 'ham it up' (7) as she wanted to play down the theatricality in order to bring into focus questions of the female role in such films. Fried pays attention to these photographs as they nicely exemplify his ideas of 'anti-theatricality'. He notes that he is not impressed by any of Sherman's later projects after her Art Forum series. Again, no surprise, I can't imagine maimed doll figures posed in sexual positions to raise questions about pornography would be Fried's cup of tea. I must say though, I was impressed to observe that Fried noted the contradictions in Sherman's work. It is both theatrical and anti-theatrical and Fried is surprisingly content with this, although as I mentioned above, the work strengthens his arguments nicely.

Fried uses Wall's piece to discuss issues of theatricality and anti theatricality in cinema. He discusses Wall's view that cinema can not be Modernist art as it provides a form of escapism and absorption. He calls cinema 'a sonambulistic approach toward utopia.' In other words, the cinema has the ability to brainwash us into worshiping popular culture (Walter Benjamin's 'The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction' comes to mind). Fried sees Wall's piece as the perfect example of cinema as anti-theatricality as there is nothing theatrical about sitting inside the 'machine' (13) that Fried call the movie theater and these photographs study the hypnotic state a cinematic experience puts us in. I agree with these points and find them rather interesting, however, what about film designed to awaken the senses and confront the public with real issues and problems, for example, Michael Moore's 'Bowling For Columbine'. What is hypnotising about a move like that? Fried claims that all three works bring to light issues of theatricality in art and the problems this causes. He urges us to view these works as separate but linked and to focus on the advantage of anti-theatricality.

Jeff Wall, 'The Destroyed Room'.

Fried goes on to discuss The Tableau using again, Wall and also Thomas Ruff and Jean-Marc Baptiste as examples. He again mentions the 'new regime' (14) and reinforces the fact that these images were made to be 'hung on the wall and looked at like paintings' (14). He discusses Wall's piece 'Destroyed Room' in reference to how these works are viewed best in person, on the gallery wall, providing what Fried believes to be a true art experience. He notes that these images are lost when framed in books. This is a valid point, as certainly these photographs are rich in detail that is muted when these pictures are shrunk. I refreshing point made by Fried was that the power of these pictures depended on the viewers ability to 'respond not just intellectually but punctually' (16). This surprised me, as Fried usually favours art work that still impresses him even his it doesn't require this response from the viewer (anti-theatrical). He discusses the work of Ruff and notes that in 1981 his photographs were significantly smaller (22x18cm) but claims that, influenced by these large scale works, he increased his pictures to a handsome 210x165cm. This is an interesting point as it show there was a trend print larger scale during this period. He then discusses the work of Jean-Marc Bustamante and this is where things get really interesting.

Bustamante, from 'Tableaux'.

The reason I found this section interesting is firstly, the discussion of the images is of paradoxes. Fried quotes the critic Criqui as what he sees as 'exactly right' about the work (19). Criqui notes that Bustamante's images do not want to invite the viewer to engage with them imaginatively. Bustamante reinforces this by stating that he wants the viewer to have a 'non-directive relationship' with the images. However, he then notes that he wants the viewer to be 'equally responsible for the work' and that he aims to make the viewer 'aware of the responsibility for what he/she is looking at. (20). So, he wants us to be engaged, yet disengaged. This connects with ideas discussed in the previous class about contradictions in Contemporaneity. The second thing I found interesting is that Bustamante notes that the reason he made his photographs large so that it would become art (22). I find it intriguing that he felt pressured to make his photographs large, again, to compete with painting and to fit into a modernist tradition of tableau in order to feel validated as an artist. I am interested in observing trends in standard photographic display size, as in terms of the Canon of photography. It seems larger scale preludes to 'serious art' whilst modest sized prints can be given an inferior status as they do not attempt to compete with painting. Though larger photographs will always receive more critical attention, I think one characteristic f the contemporary is a shift in how art is perceived as previously mentioned. Due to globalization and the Internet, a large painting style piece is no longer necessary. Finally, Fried makes a confusing statement. Despite is contempt for Minimalism, what he calls 'so called art', he compares Bustamante's pieces to such art work (23) and then titles it 'the most original and impressive in decades' (23). I suppose Freid finds it less intimidating if the techniques of Minimalism are muted and framed within photographic boundaries.

Following the Tableau, Fried moves on to the topic of the 'Contre'. He does so in order to discuss the connection of literature to imagery (I would assume, again, in order to connect photography to a serious and respected art tradition, the art of writing). The first text he discusses is 'Adelaide: Ou La Femme Morte D'Amour', meaning in English, the woman who died from love. In this book, Fried envisions two tableaus from the story. One, a picture of Adelaide's love interest wholly absorbed in his religious work, the other, an image of Adelaide's death following her loves refusal to look at her, as he was pretending to be absorbed to avoid her gaze. So why in the world is he talking about a story from the 1600's? How is that going to have anything to do with the Contemporary? Fried discusses the trend in France in 1750 of absorptive paintings. For a work of art to be acceptable at this time, the subject (especially the women) we supposed to be completely engrossed in their actions, ignorant of the 'outside' or the audience. He notes that confrontational painting (such as Manet's 'Olympia') pointed out the folly of such theatricality, as paintings function was to be looked upon.

Manet, 'Olympia'.

He discusses issues of 'falseness vs truthfulness', and here he makes his point for discussing this story. He feels it is stories like 'Adelaide' that hold responsibility for dramatizing fiction, to pretend there is now audience, not painting. He feels that this story can paint a picture, so to speak, that we do not question, whilst if we to look at this story translated onto canvas, it would seem false. I think this is a fairly valid point that I would more or less agree with. However, I fail to see the problem with painting or photography as fiction that is meant to be real. I enjoy many works that are built this way and don't feel it is bound to one medium.

Fried moves on to discuss another book, 'Temple of Dawn' by Mishima from the early 70's. Fried is interested in this text because it concerns notions of Voyeurism, which he seems as similar to photographic trope. This is a rather odd story about elderly man, Honda spying on a young princess. The main issue of the story is the Protagonist's dilemma of wanting to look at the young woman without effecting or changing her world. He knows the only way this would happen is if he did not exist, which obviously, is impossible. Fried sees the secret invasion of the princess's world as similar to photography that captures it subjects in secret, or unaware. He notes that the moral question of the Protagonist's voyeurism is similar to those that arose in the late 70's in relation to practices of street photography. Honda's desire to be invisible, yet still capture the image relates directly to practices of candid photography. Many photographers want to capture 'natural' images, without their presence intruding on, or influencing the situation. Photographers are at an advantage in the Contemporary world. People are used to cameras. Photographing one another is a widespread social practice, camera are smaller, quieter and faster (at least in the commercial sense). However issues of personal privacy and surveillance are magnified. We are photographed and filmed in secret all throughout the day and the Internet poses a new threat to identity protection, therefore the moral question of candid photography becomes even more complicated. I think the moral dilemma of photographing a world in secret is one that resonates through all eras of photography.

Fried moves on to discuss another book, 'Temple of Dawn' by Mishima from the early 70's. Fried is interested in this text because it concerns notions of Voyeurism, which he seems as similar to photographic trope. This is a rather odd story about elderly man, Honda spying on a young princess. The main issue of the story is the Protagonist's dilemma of wanting to look at the young woman without effecting or changing her world. He knows the only way this would happen is if he did not exist, which obviously, is impossible. Fried sees the secret invasion of the princess's world as similar to photography that captures it subjects in secret, or unaware. He notes that the moral question of the Protagonist's voyeurism is similar to those that arose in the late 70's in relation to practices of street photography. Honda's desire to be invisible, yet still capture the image relates directly to practices of candid photography. Many photographers want to capture 'natural' images, without their presence intruding on, or influencing the situation. Photographers are at an advantage in the Contemporary world. People are used to cameras. Photographing one another is a widespread social practice, camera are smaller, quieter and faster (at least in the commercial sense). However issues of personal privacy and surveillance are magnified. We are photographed and filmed in secret all throughout the day and the Internet poses a new threat to identity protection, therefore the moral question of candid photography becomes even more complicated. I think the moral dilemma of photographing a world in secret is one that resonates through all eras of photography.

Jeff Wall, 'Dead Troops Talk'.

Finally, Fried discusses 'Regarding the Pain of Others' by Susan Sontag. In this book length essay, Sontag explains her view that documentary war photography unnecessary and suggests that art photography dealing with war is the only way we can be truly touched by such images. She sees Wall's 'Dead Troops Talk' as the ultimate image of war in a contemporary world. Sontag admires this image as none of the soldiers gaze out of the frame and therefore the image reminds us that 'we' (we being those who are fortunate enough to have never experienced war) have no idea what the people have been through and there is no point trying to, as it is truly unimaginable. Fried agrees with Sontag and enjoys this image as it is what he calls 'anti-theatrical'. He is interested in the 'to-be-looked-at-ness' of the image.

Fried concludes by claiming that the images that are currently, in his opinion, significant, are those such as 'Dead Troops Talk'. They are images which fall under a Diderotian thematic of absorption. Fried stays true to his view of 'anti-theatrical' images as those which are superior. He claims that once the concept of a world that would be contaminated simply by being beheld emerged, this esthetic found its home in photography. In other words, Fried sees photography as the perfect medium for his anti-theatrical theory and this is why he is so attracted to it. The essence of photography is to look at the world. However, photographs are more diverse than Fried would like to believe. Photography can confront, but Fried is not interested in this. Fried could have easily called this book, 'The Reason I love Photography Suddenly Is Because It Started To Remind Me Of The Paintings I Like.' Fried champions anti-theatrical painting and therefore, anti-theatrical photography. Photography matters, but not because of the trend of larger scale printing, photography mattered long before that occurred. Contemporary photography has a power that does not require a huge print to get its point across. People are enlightened by photographs they see on their computer screens and in books everyday. Of course, photography deserves the respect of being shown in its full capacity in a gallery space (or wherever it is intended to be shown), but I think Fried is missing out on the bigger picture (excuse the pun) if large scale prints and anti-theatrical stand points are the only reason he see photography as valid.

I won't crucify Fried too much though, as firstly, this type of photography is amazing. I remember the first time I saw a Wall piece in all its large, illuminated glory and I really was gobsmacked. Secondly, this book was written in 2008, but I think its extremely important to note.. Fried is 71 years of age. (Now I feel bad, as if I was bullying my Grandad.. dammit.) Contemporary photography is made by young artists, connected to a young world of emerging trends and practices. I doubt Fried sits at home on his Mac browsing through Flickr and Tumblr to see what the youngest photographers are coming up with. Fried writes about what he sees mostly in the mainstream and in this context, I appreciate his view and think this is a valid and useful text.

Fried concludes by claiming that the images that are currently, in his opinion, significant, are those such as 'Dead Troops Talk'. They are images which fall under a Diderotian thematic of absorption. Fried stays true to his view of 'anti-theatrical' images as those which are superior. He claims that once the concept of a world that would be contaminated simply by being beheld emerged, this esthetic found its home in photography. In other words, Fried sees photography as the perfect medium for his anti-theatrical theory and this is why he is so attracted to it. The essence of photography is to look at the world. However, photographs are more diverse than Fried would like to believe. Photography can confront, but Fried is not interested in this. Fried could have easily called this book, 'The Reason I love Photography Suddenly Is Because It Started To Remind Me Of The Paintings I Like.' Fried champions anti-theatrical painting and therefore, anti-theatrical photography. Photography matters, but not because of the trend of larger scale printing, photography mattered long before that occurred. Contemporary photography has a power that does not require a huge print to get its point across. People are enlightened by photographs they see on their computer screens and in books everyday. Of course, photography deserves the respect of being shown in its full capacity in a gallery space (or wherever it is intended to be shown), but I think Fried is missing out on the bigger picture (excuse the pun) if large scale prints and anti-theatrical stand points are the only reason he see photography as valid.

I won't crucify Fried too much though, as firstly, this type of photography is amazing. I remember the first time I saw a Wall piece in all its large, illuminated glory and I really was gobsmacked. Secondly, this book was written in 2008, but I think its extremely important to note.. Fried is 71 years of age. (Now I feel bad, as if I was bullying my Grandad.. dammit.) Contemporary photography is made by young artists, connected to a young world of emerging trends and practices. I doubt Fried sits at home on his Mac browsing through Flickr and Tumblr to see what the youngest photographers are coming up with. Fried writes about what he sees mostly in the mainstream and in this context, I appreciate his view and think this is a valid and useful text.

No comments:

Post a Comment