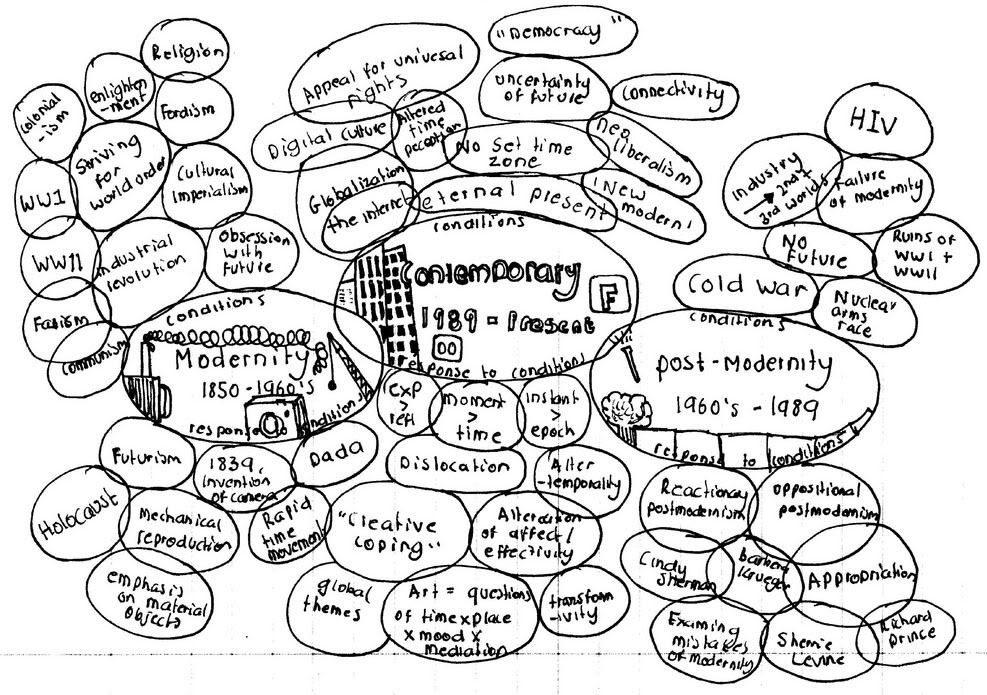

As mentioned in the previous class, it is true that for quite some time, many scholarly articles, books and institutions seemed to conclude that photography went mute after the Berlin Wall came down, leaving only ghostly traces of Cindy Sherman's monochrome figure lurking with an uncertainty in her eye. I do no think this is anything to do with a decline in photographic practice at the time. Rather, I believe Post Modernism came to a rapid and dramatic close during this period of time. As the Berlin wall fell and the Cold War concluded, a rather uneasy and frightening time for many climaxed and along with this went Post Modernity. What the world of art was left with was the option to grasp something completely and utterly new. An era cleansed of war, at least temporarily, allowed artists to consider other facets of life that weren't overshadowed by the possibility of a Nuclear bomb bringing everything to a devastating close. With Modernity and Post Modernity secreting into the silence of the past, we are left with no other option but to throw ourselves into the present, or what Terry Smith has coined as 'Contemporaneity'.

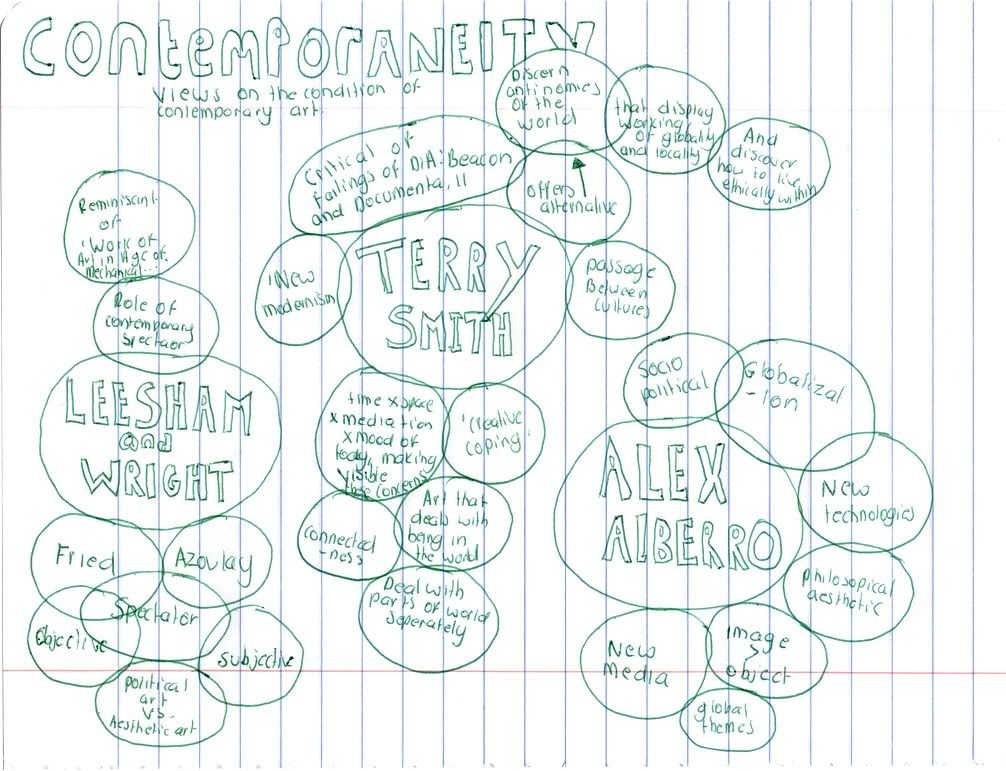

The word 'Contemporary' is a rather ambiguous for a number of reasons. Firstly, it cannot be tied down to any one era, as what was contemporary in the 1800's, for example, is no longer so, however, we use the same word to describe what is currently contemporary. Secondly, contemporary has come to override a number of other terms, giving it multiple uses. 'Modern Art', once a term used to described anything new is now described as 'Contemporary Art', 'Avant Garde' is not a term regularly employed in galleries currently either, again being surpassed by the term contemporary. Contemporaneity is more a set of conditions and a reaction to these conditions, all of which are current and active in our world. 'The Contemporary' is not a time period or era, or even a certain style of art. Rather, the contemporary associates itself with issues of time, space and mood. We are currently living and experiencing the contemporary. It is something new, something ground breaking and its happening all around us. Studying what defines Contemporary Photography and how it works in conjunction to our current time period, which, for now we will call Contemporary is something that to me, is an obvious advantage. Why any young artist wouldn't want to immerse themselves in their own time and learn more about its workings worries me. Studying the contemporary is obviously beneficial to any artist who wants to be successful in this time period. Of course, an in depth knowledge its predecessors, Modernity and Post Modernity is an essential part of this too. I think as young artists it is our duty to educate ourselves of these periods in art history as well as involving ourselves in what Terry Smith calls a time that is 'pregnant with the present.'

How can we separate these terms?

In addition to Globalization, Alberro emphasizes the importance of new technologies and the effect of these technologies on contemporary art. One of his most interesting points is that the image has know come to reign over the object. Perhaps I'm biased as a photographer, but I would concur that art is no longer dominant as a tangible object in a gallery, but rather a readily accessible set of pixels available at the touch of a button on your home computer. The possibilities provided and the implications of this is astounding for young artists. This ties into Alberro's point about the reinvention of communication and time that is bound up in the revolution of the World Wide Web.

Interestingly, Alberro also touches on the current trend of contemporary artists to create a fictional reality for their work, almost as a rejection of the overwhelming hyper-reality of contemporaneity. I find this to be one of the most interesting themes on contemporary art and am interested in how it has become accepted and normalised to reject and in some cases mock reality in favour of a creation of a new one. Other artists create situations almost mimicking reality but injecting their own fictionalized stories as in the work of William Kentridge or the Atlas group (Walid Raad). Of course, this isn't a new practice, as artists have worked this way since practically the beginning of photography. However, the ability of digital technology or new media to render this work believable like never before is something that allows contemporary art to stand apart from the art of the modern or post modern era. Also, the pool of resources now available is a huge advantage for anyone who wishes to work this way. One of my favourite artists who works in this respect is Nikki S .Lee, who spends her days taking on the persona of other people from different cultures. (I should note that Lee began this work in 1997, so the clothes, social groups, snap shot aesthetic, etc, are slightly out of date already and more suited to the nineties, but Lee is dealing with contemporary themes such as Smith's 'Passage Between Cultures' and Globalization, themes that were only emerging during the time of this project and could easily be updated to fit into contemporary culture if she updated the social groups and perhaps used a cheap digital camera).

Alberro mentions a shift from the cognitive to the affective, where contemporary artists place emphasis on the experience of an art work being more important than understanding an art work. This is a valid point. I think its interesting to observe that much of contemporary art relies on a certain shock factor due to an overpopulation of photographers, many with similar influences. However, I do not think it is wise to disregard the need to 'understand art' for creator or spectator. After the shock of a tabooed subject matter has been explored, what is left for the artist to work with? One's practice must have more resonance than this. Certainly, there has been a shift in the way the spectator engages with the art work and to ignore this is to ignore one of the largest embodiments of contemporaneity.

Alberro discusses many of the factors that allow contemporary art to come into existence, but what about a practical survey of what defines contemporary art and exemplifies its failing and successes? The text by Terry Smith attempts to outline this. Smith divides the contemporary into two sections, the 'old modern in new clothes' and 'Passages Between Cultures'. Both terms seem rather ambiguous. Smith claims the contemporary is the new modern because it takes itself to be the 'high cultural style of the time' (688). Of course, this is an obvious observation and doesn't really tell me much about the time we live in other than that it is full of new and emerging technologies and artistic practices that consider themselves superior to their predecessors. This could generally apply to any era. He continues on to criticise museums such as MOMA for its 'confused gesturings' (688) when trying to grasp contemporary art and slates DIA:Beacon for abusing its 'Old Master elegance' status in housing the large scale 'Cremaster' exhibition in 2003. Smith seems frustrated by the strand of contemporary art that is grasping to allign itself with a continuting modernist timeline and call for a new strategy.

When discussing the other strand, 'Passage Between Cultures' he uses Shirin Neshat's 2001 video 'Passage' and Ayanah Moor's 2004 wall installation 'Never.Ignorarant.Gettin' Goals.Accomplished. as examples. Both art works deal with issues of gender, racial and cultural identity and alienation in the global world. Smith questions if its art works such as these, works that deal with being in the world, are what identify art as contemporary. He also notes that these types of art works dominated the Documenta 11 exhibition and caused tension and division in trying to accommodate each area of the globalized world's differing view points. This is why he calls this strand of art work a Passage Between Cultures, as exhibitions such as Documenta 11 are an exchange of cultural practices and ideologies, some of which, of course, clash. He notes that such conflicts demonstrate the 'limits out of which the postcolonial, post cold war, postideological, transnational, deterritorialized, diasporic, global world has been written' (693-694). Again, Smith has contempt for such large scale exhibitions that seem to try cover too much ground.

Smith details the events of both exhibitions extensively and does not shy away from pointing out the failures of both. Smith calls one a "tiring juggernaut" and the other and "swarming attack of vehicles". He sees DIA: Beacon as too assuming of contemporary art as the highest cultural style and too over reaching in its large scale exhibition. He sees Documenta 11 as an overload of ideas and a clash of personal ideologies of modernity vs contemporaneity.

Thus, Smith comes to an interesting and valid conclusion: neither exhibitions addresses the 'changes in actual artistic practices that have, for arguably three decades now, marked out more and more artistic production as distinctively contemporary - as opposed to that which continues to be made in modernist, or even postmodern modes' (695). Smith proposes an alternative plan to construct the frame work of a large scale exhibition of contemporary art. He sees the answer as neither a middle path between the two exhibitions discussed or an opposing models. Rather, Smith believe we should recognize the 'energy of their profound contention' and see all elements that make up the contemporary world as 'antinomies'. I think what Smith is saying is that the contemporary era cannot be summarized in one large exhibition. DIA:Beacon and Documenta 11 made the same mistakes as Family of Man did in 1955 by attempting to summarise the whole world, which really is impossible, confusing and irritating.

In the second part of Smith's article, he defines a more practical appraoch to defining the contemporary. Smith believe that true contemporary artists are 'committed to an art that turn on long term, exemplary projects that...display the working of globality and locality, and that imagine ways of living ethically within them' (698). He characterises contemporary art as that which considers questions of 'time, place, mediation and mood' (700), or what he sees today as '(alter)temporality, (dis)location, tranformivity, within the hyper real and the altercation of affect/effectivity' (700). To Smith, this is 'Contemporaneity'. As useful as comparing large scale exhibitions can be, I find this response much more engaging and practical to me as a young artist attempting to define contemporary art. I understand Smith's definition of Contemporaneity on a realistic level and can see how it fits into his proposal as it provides practical answers of how to see the world as what he calls 'antinomies'. Smith also discusses a sense of 'connectedness' (703) and the notion of the 'human web' (704). I think this is important as it is impossible to ignore the expanding interweave of artistic practice through platform such as the Internet. These are the elements which directly effect our practice as young artists today. He notes that classic conceptions of modernity and post modernity cannot stretch to 'carry this degree of spin out' (706), a term I find very fitting for contemporaneity. We are spinning out, not quite sure where we are going and where we are to end up, but its ever so enjoyable. Finally, I found Smith's notion of a 'permanent seeing of after math' post cold war as intriguing. He claims we are in 'Ground Zero everywhere'. It is not that we are free of history but we are in a time of a new era, unsure of its direction, with only the past as a guide. We are coming to terms with the aftermath of modernity and post modernity but we are not defined by it. As a reaction to this 'universal condition' we respond with 'creative coping' (707).

Following this, I read the text by Noam Leshem and Lauren A. Wright. This text gives an overview of two recently published and important books that deal with issues surrounding contemporaneity. The books are Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before by Michael Fried and The Civil Contact of Photography by Arella Azoulay. The text was useful as it is a small and accessible comparison of two opposing views of contemporary art, a refreshing read after tackling Smith's twenty six page discussion. Both texts deals with the aesthetic experience of viewing a photograph and how this effects the viewer and how the spectator should react to certain types of contemporary art. Fried's view is that the most important type of photography currently is that which is of large scale and allows the viewer to act as the passive voyeur, comfortably surveying a photograph and coming to ones own conclusions. He champions Jeff Wall in this respect, as many critics do and discusses the work of other large scale artists such as Gursky, Dijkstra, Demand, etc. Freid frames this type of art work withing the work of great painter's such as Manet. The authors note that Fried is keen to frame this work within his 'modernist project' (115) is one I am in agreement with. Fried's focusing on the aesthetic reminds me of Wall's view in 'Marks Of Indifference'. The historical context and complex subject matters of the photographs are ignored and the visual value of the piece and the spectator's experience is placed above artistic intent. For example, Fried sees Dijkstra's project on young women at the beach as a photograph lacking theatricality and simply characterised by a 'to-be-seenness.' I think Dijkstra had a lot more in mind than creating a pretty picture. Fried compares Dijkstra's photographs to Arbus', but prefers the former as they are 'nicer to look at' (116) and therefore do not raise an ethical issues. This quote conveys the weakness of Fried's argument. Fried wants a photograph that is nice to look at and doesn't make him feel uncomfortable. He is afraid to be confronted by photography and therefore champions a passive photograph that he can control over a confrontational photograph. Thus, he reduces the work of a great photographer such as Dijkstra to a pretty picture, when in fact she is dealing with complex issues of adolescence and femininity in a globalized world. Fried is clinging to a grand narrative, modernist viewpoint where art should not attempt to confront the viewer, but only please the eye and to my delight, both authors criticize this.

From Rineke Dijkstra's 'Beach Portraits'.

In sharp contrast, Azoulay places great emphasis on a connection between the viewer and photograph and criticises the 'passive beholder'. (117) Azoulay's work deals with images of Palestinian women and men and how their image has been constructed by the media. She contests Sontag's point that the viewer has been over saturated by images of war and strives to confront the public with a powerful image of her people, questioning and conversing with the viewer, forcing them to contemplate the position the subject is in, or has been put in. The author's claim Azoulay's photographs have an 'unwritten yet clearly identifiable contract between its participants.' Azoulay's photography is an attempt to force the viewer into response and personally, I find this type of photography powerful in its message and moving in its confrontation. However, what Fried seems to ignore is that even in this situation, the spectator is still in control. As Azoulay notes, 'without a willing labour of spectatorship, the photograph is left as a flawed statement.. an impaired attempt to convey a sense of urgency' (117). Azoulay's argument is not perfect either, as she fails to mention the risk of overexposure to the image despite disagreeing with Sontag. She also fails to urge her readers to respond more actively to photography such as this.

Fried and Azoulay's take both arguments to the extreme. Fried argues the right of the viewer to passively survey a photograph and emphasizes the importance of an aesthetically pleasing piece whilst Azoulay urges the need for politcally engaged and confrontational photography that attempts to force the spectator to react. Both arguments are important as the highlight two views on contemporary art. There will always be spectators, such as Fried who prefer to dictate their own viewing, refusing to be overcome by a photograph. This poses a threat to many political artists such as Azoulay and the message they are trying to convey. However, such a strong view such as Azoulays, that art such be politcally engaged and awaken the viewer leaves the spectator with little choice and undermines practices of documentary photographer or photographer's who deal with themes outside of the political. I feel that Freid's argument harks back to a modernist tradition as previously discussed, whilst Azoulay's is reminiscint of the post modern era as she is questioning the 'norm' of war photography and media representations and many post modern artists in that era before. However, both books are dealing with contemporary art and give a useful overview of two views from an established viewpoint.

As different as the three articles are, what they all provide is information on how to understand the contemporary or Contemporaneity. Alberro's text provides a brief overview of some of the socio-political conditions which allow contemporary art to come into existence, such as globalization, an important concept. Smith's text provides an extensive comparision of various exhibitions attemtping to deal with the contemporary and outlines their failings. He provides an interesting alternative which contains mainy of the characteristics of contemporary art which I found to be the most interesting part of his article. Finally, Leesham and Wright's text magnifies the views of two authors discussing two different views of contemporary art. Comparing three articles that focus on such different areas is difficult, but gives a wide spread view of the many different facets that make up contemporary art.

Defining the era we live in, perhaps the era of Contemporaneity or pinpointing what makes contemporary art what it is, is difficult to discuss extensivley in a blog entry. However, I have been left with some interesting points to ponder over and consider in realtion to contemporary art, I personally think these are the most important points we are left with:

And yes, I realize this was a very long entry and it probably bored you to tears. I'll get better at this, I promise. I'll finish by saying, I love living and experiencing 'the contemporary' and so should you because its our time as artists and it won't last forever. Its ours, so why not nourish it? Whatever 'it' is. I love seeing new barriers being broken down and the camera being used to smash through even more taboos than ever. And of course, seeing old themes being revived and encoporated into a new time.

No comments:

Post a Comment